Dynamic Modeling Considerations

There are three aspects that the user should consider when preparing a FLAC3D model for a dynamic analysis: 1) dynamic loading and boundary conditions; 2) wave transmission through the model; and 3) mechanical damping. This section provides guidance on addressing each aspect when preparing a FLAC3D data file for dynamic analysis. Solving Dynamic Problems and Verification Problems illustrate the use of most of the features discussed here.

Dynamic Loading and Boundary Conditions

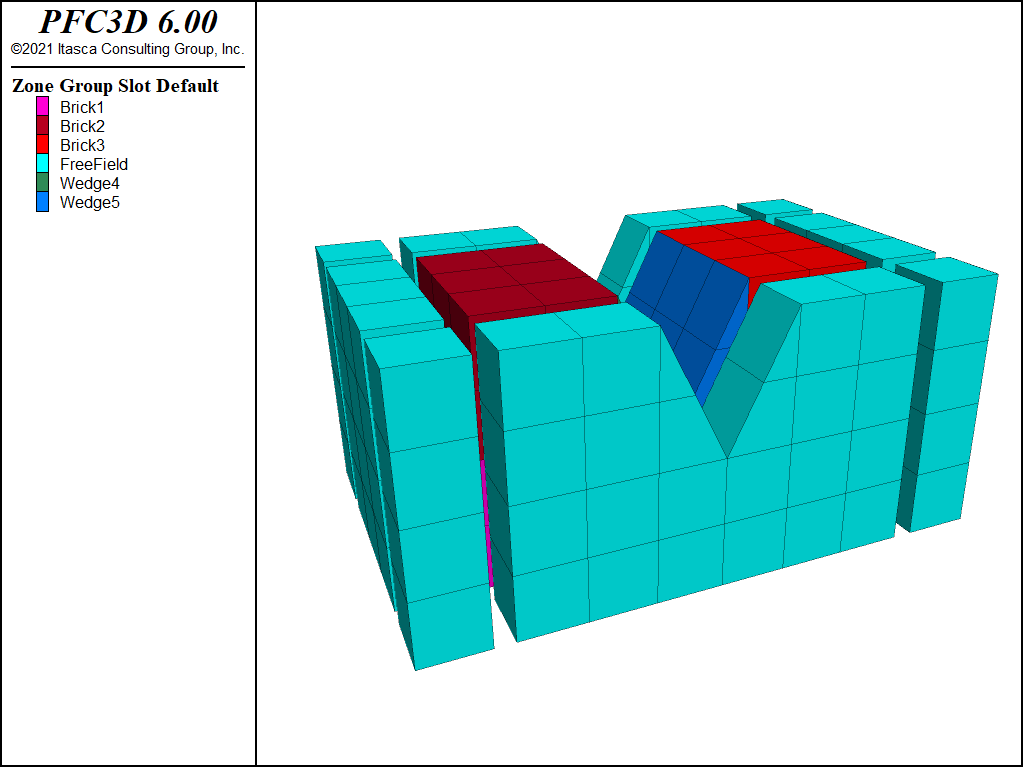

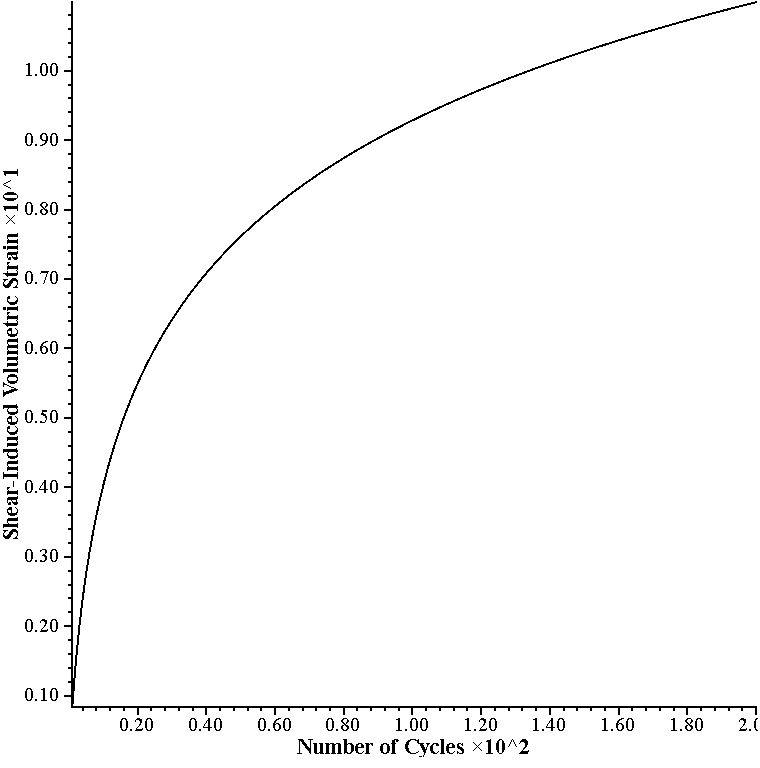

FLAC3D models a region of material subjected to external and/or internal dynamic loading by applying a dynamic input boundary condition at either the model boundary or internal gridpoints. Wave reflections at model boundaries may be reduced by specifying quiet (viscous) or free-field boundary conditions. The types of dynamic loading and boundary conditions are shown schematically in Figure 1; each condition is discussed in the following sections.

Application of Dynamic Input

In FLAC3D, the dynamic input can be applied in one of the following ways:

- an acceleration history;

- a velocity history;

- a stress (or pressure) history; or

- a force history.

Dynamic input is usually applied to the model boundaries with the zone face apply

command. Accelerations, velocities, and forces can also be applied to interior gridpoints by

using the zone gridpoint fix command. Note that the free-field boundary, shown in

Figure 1, is not required if the only dynamic source is within

the model (see Free-Field Boundaries).

The history function for the input is treated as a multiplier on the value specified with the

zone face apply command. The history multiplier is assigned with the history

keyword and can be in one of two forms:

- a table defined by the

tablecommand; or- a FISH function.

Figure 1: Types of dynamic loading and boundary conditions available in FLAC3D.

With table input, the multiplier values and corresponding time values are entered as

individual pairs of numbers in the specified table; the first number of each pair is assumed

to be a value of dynamic time. The time intervals between successive table entries need not

be the same for all entries. The table import command allows files containing time

histories (such as earthquake records) to be imported into a specified FLAC3D table. If a

FISH function is used to provide the multiplier, the function must access dynamic time

within the function, using the FLAC3D scalar variable zone.dynamic.time.total, and

compute a multiplier value that corresponds to this time. The example of Shear Wave

Propagation in a Vertical Bar provides an example of dynamic loading derived

from a FISH function.

Dynamic input can be applied in the \(x\)-, \(y\)-, or \(z\)-direction corresponding to the \(x\)-, \(y\)-, \(z\)-axes for the model, or in the normal and shear directions to the model boundary.

One restriction when applying velocity or acceleration input to model boundaries is that these boundary conditions cannot be applied along the same boundary as a quiet (viscous) boundary condition (compare Figure 1-a to Figure 1-b), since the effect of the quiet boundary would be nullified. To input seismic motion at a quiet boundary, a stress boundary condition is used (i.e., a velocity record is transformed into a stress record and applied to a quiet boundary). A velocity wave may be converted to an applied stress using the formula

or

where:

| \(\sigma_n\) | = applied normal stress; |

| \(\sigma_s\) | = applied shear stress; |

| \(\rho\) | = mass density; |

| \(C_p\) | = speed of \(p\)-wave propagation through medium; |

| \(C_s\) | = speed of \(s\)-wave propagation through medium; |

| \(v_n\) | = input normal particle velocity; and |

| \(v_s\) | = input shear particle velocity. |

\(C_p\) is given by

and \(C_s\) is given by

The formulae assume plane-wave conditions. The factor of two in Equations (1) and (2) accounts for the fact that the applied stress must be double that which is observed in an infinite medium, since half the input energy is absorbed by the viscous boundary. The formulation is similar to that of Joyner and Chen (1975).

The following example illustrates wave input at a quiet boundary:

Baseline Correction

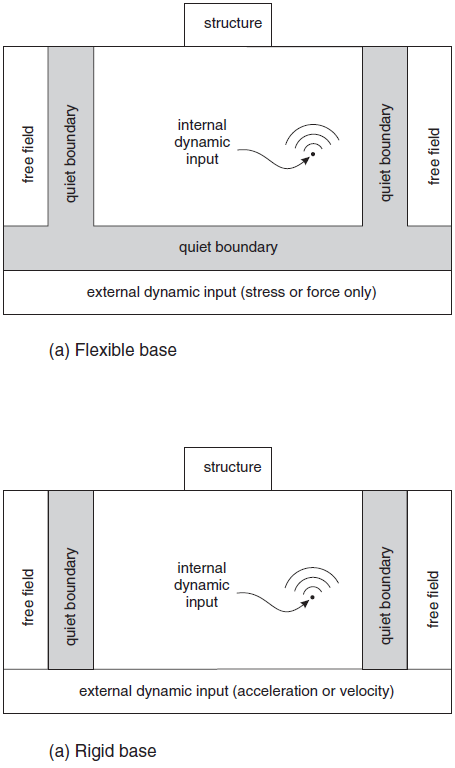

If a “raw” acceleration or velocity record from a site is used as a time history, the FLAC3D model may exhibit continuing velocity or residual displacements after the motion has finished. This arises from the fact that the integral of the complete time history may not be zero. For example, the idealized velocity waveform in Figure 2a may produce the displacement waveform in Figure 2b when integrated. The process of “baseline correction” should be performed, although the physics of the FLAC3D simulation usually will not be affected if it is not done. It is possible to determine a low frequency wave (for example, Figure 2c) which, when added to the original history, produces a final displacement that is zero (Figure 2d). The low frequency wave in Figure 2c can be a polynomial or periodic function, with free parameters that are adjusted to give the desired results. An example baseline correction function of this type is given as a FISH function in Dynamic Conditions and Simulation.

Baseline correction usually applies only to complex waveforms derived, for example, from field measurements. When using a simple, synthetic waveform, it is easy to arrange the process of generating the synthetic waveform to ensure that the final displacement is zero. Normally, in seismic analysis, the input wave is an acceleration record. A baseline-correction procedure can be used to force both the final velocity and displacement to be zero. Earthquake engineering texts should be consulted for standard baseline correction procedures.

An alternative to baseline correction of the input record is the application of a displacement shift at the end of the calculation if there is a residual displacement of the entire model. This can be done by applying a fixed velocity to the mesh to reduce the residual displacement to zero. This action will not affect the mechanics of the deformation of the model.

Computer codes to perform baseline corrections are available from several websites (for example, http://nsmp.wr.usgs.gov/processing.html).

Figure 2: The baseline-correction process.

Quiet Boundaries

The modeling of geomechanics problems involves media which, at the scale of the analysis, are better represented as unbounded. Deep underground excavations are normally assumed to be surrounded by an infinite medium, while surface and near-surface structures are assumed to lie on a half-space. Numerical methods relying on the discretization of a finite region of space require that appropriate conditions be enforced at the artificial numerical boundaries. In static analyses, fixed or elastic boundaries (e.g., represented by boundary-element techniques) can be realistically placed at some distance from the region of interest. In dynamic problems, however, such boundary conditions cause the reflection of outward propagating waves back into the model, and do not allow the necessary energy radiation. The use of a larger model can minimize the problem, since material damping will absorb most of the energy in the waves reflected from distant boundaries. However, this solution leads to a large computational burden. The alternative is to use quiet (or absorbing) boundaries. Several formulations have been proposed. The viscous boundary developed by Lysmer and Kuhlemeyer (1969) is used in FLAC3D. It is based on the use of independent dashpots in the normal and shear directions at the model boundaries. The method is almost completely effective at absorbing body waves approaching the boundary at angles of incidence greater than 30°. For lower angles of incidence, or for surface waves, there is still energy absorption, but it is not perfect. However, the scheme has the advantage that it operates in the time domain. Its effectiveness has been demonstrated in both finite-element and finite-difference models (Kunar et al. 1977). A variation of the technique proposed by White et al. (1977) is also widely used.

More efficient energy absorption (particularly in the case of Rayleigh waves) requires the use of frequency-dependent elements, which can only be used in frequency-domain analyses (e.g., Lysmer and Waas 1972). These are usually termed “consistent boundaries” and involve the calculation of dynamic stiffness matrices coupling all the boundary degrees-of-freedom. Boundary-element methods may be used to derive these matrices (e.g., Wolf 1985). A comparative study of the performance of different types of elementary, viscous, and consistent boundaries was documented by Roesset and Ettouney (1977).

The quiet-boundary scheme proposed by Lysmer and Kuhlemeyer (1969) involves dashpots attached independently to the boundary in the normal and shear directions. The dashpots provide viscous normal and shear tractions given by

where \(v_n\) and \(v_s\), are the normal and shear components of the velocity at the boundary, \(\rho\) is the mass density, and \(C_p\) and \(C_s\) are the \(p\)- and \(s\)-wave velocities.

These viscous terms can be introduced directly into the equations of motion of the gridpoints lying on the boundary. A different approach, however, was implemented in FLAC3D, whereby the tractions \(t_n\) and \(t_s\) are calculated and applied at every timestep in the same way boundary loads are applied. This is more convenient than the former approach, and tests have shown that the implementation is equally effective. The only potential problem concerns numerical stability, because the viscous forces are calculated from velocities lagging by half a timestep. In practical analyses to date, no reduction of timestep has been required by the use of the nonreflecting boundaries. Timestep restrictions demanded by small zones are usually more important.

Dynamic analysis starts from some in-situ condition. If a fixed boundary is used while generating the static stress state, this boundary condition can be replaced by quiet boundaries; the boundary gridpoints will be freed, and the boundary reaction forces will be automatically calculated and maintained throughout the dynamic loading phase. However, changes in static loading during the dynamic phase should be avoided. For example, if a tunnel is excavated after quiet boundaries have been specified on the bottom boundary, the whole model will start to move upward. This is because the total gravity force no longer balances the total reaction force at the bottom that was calculated when the boundary was changed to a quiet one. If a stress boundary condition is used during the static solution, a stress boundary condition of opposite sign must also be applied over the same boundary when the quiet boundary is applied for the dynamic phase. This will allow the correct reaction forces to be in place at the boundary for the dynamic calculation.

Quiet boundary conditions can be applied in the global coordinate directions, or along

inclined boundaries, in the normal and shear directions using the zone face apply

command with appropriate keywords (quiet-normal, quiet-dip,

quiet-strike for one component or quiet for all three components). When using

the zone face apply command to install a quiet boundary condition, remember that the

material properties used in Equations (5) and (6) are obtained from

the zones immediately adjacent to the boundary. Thus, appropriate material properties for

boundary zones must be in place at the time the zone face apply command is given, in

order for the correct properties of the quiet boundary to be stored.

Quiet boundaries are best-suited when the dynamic source is within a grid. Quiet boundaries should not be used alongside boundaries of a grid when the dynamic source is applied as a boundary condition at the top or base, because the wave energy will “leak out” of the sides. In this situation, free-field boundaries (described below) should be applied to the sides.

Free-Field Boundaries

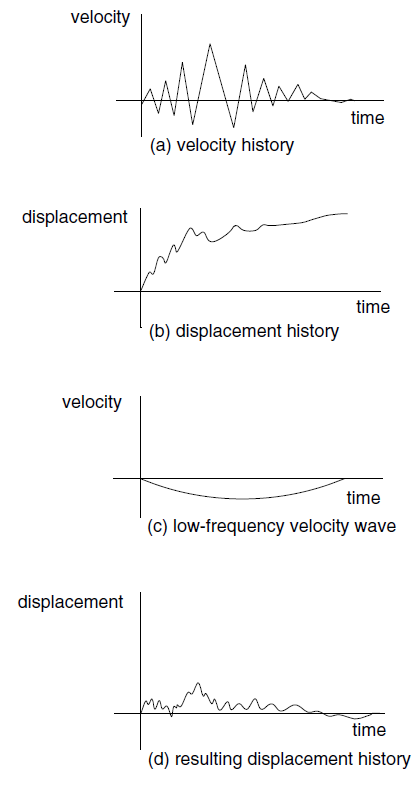

Numerical analysis of the seismic response of surface structures such as dams requires the discretization of a region of the material adjacent to the foundation. The seismic input is normally represented by plane waves propagating upward through the underlying material. The boundary conditions at the sides of the model must account for the free-field motion that would exist in the absence of the structure. In some cases, elementary lateral boundaries may be sufficient. For example, if only a shear wave were applied on the horizontal boundary, AC (shown in Figure 3), it would be possible to fix the boundary along AB and CD in the vertical direction only (see the example in Shear Wave Loading of a Model with Free-Field Boundaries). These boundaries should be placed at distances sufficient to minimize wave reflections and achieve free-field conditions. For soils with high material damping, this condition can be obtained with a relatively small distance (Seed et al. 1975). However, when the material damping is low, the required distance may lead to an impractical model. An alternative procedure is to “enforce” the free-field motion in such a way that boundaries retain their non-reflecting properties (i.e., outward waves originating from the structure are properly absorbed). This approach was used in the continuum finite-difference code NESSI (Cundall et al. 1980). A technique of this type involving the execution of free-field calculations in parallel with the main-grid analysis was developed for FLAC3D.

The lateral boundaries of the main grid are coupled to the free-field grid by viscous dashpots to simulate a quiet boundary (see Figure 3), and the unbalanced forces from the free-field grid are applied to the main-grid boundary. Both conditions are expressed in Equations (7), (8), and (9), which apply to the free-field boundary along one side-boundary plane with its normal in the direction of the \(x\)-axis. Similar expressions may be written for the other sides and corner boundaries:

where:

| \(\rho\) | = | density of material along vertical model boundary; |

| \(C_p\) | = | \(p\)-wave speed at the side boundary; |

| \(C_s\) | = | \(s\)-wave speed at the side boundary; |

| \(A\) | = | area of influence of free-field gridpoint; |

| \(v_x^m\) | = | \(x\)-velocity of gridpoint in main grid at side boundary; |

| \(v_y^m\) | = | \(y\)-velocity of gridpoint in main grid at side boundary; |

| \(v_z^m\) | = | \(z\)-velocity of gridpoint in main grid at side boundary; |

| \(v_x^{\rm ff}\) | = | \(x\)-velocity of gridpoint in side free field; |

| \(v_y^{\rm ff}\) | = | \(y\)-velocity of gridpoint in side free field; |

| \(v_z^{\rm ff}\) | = | \(z\)-velocity of gridpoint in side free field; |

| \(F_x^{\rm ff}\) | = | free-field gridpoint force with contributions from the \(\sigma_{xx}^{\rm ff}\) stresses of the free-field zones around the gridpoint; |

| \(F_y^{\rm ff}\) | = | free-field gridpoint force with contributions from the \(\sigma_{xy}^{\rm ff}\) stresses of the free-field zones around the gridpoint; and |

| \(F_z^{\rm ff}\) | = | free-field gridpoint force with contributions from the \(\sigma_{xz}^{\rm ff}\) stresses of the free-field zones around the gridpoint. |

In this way, plane waves propagating upward suffer no distortion at the boundary because the free-field grid supplies conditions that are identical to those in an infinite model. If the main grid is uniform, and there is no surface structure, the lateral dashpots are not exercised because the free-field grid executes the same motion as the main grid. However, if the main-grid motion differs from that of the free field (due to, say, a surface structure that radiates secondary waves), then the dashpots act to absorb energy in a manner similar to quiet boundaries.

Figure 3: Model for seismic analysis of surface structures and free-field mesh.

In order to apply the free-field boundary in FLAC3D, the model must be oriented such that the base is horizontal and its normal is in the direction of the \(z\)-axis, and the sides are vertical and their normals are in the direction of either the \(x\)- or \(y\)-axis. If the direction of propagation of the incident seismic waves is not vertical, then the coordinate axes can be rotated such that the \(z\)-axis coincides with the direction of propagation. In this case, gravity will act at an angle to the \(z\)-axis, and a horizontal free surface will be inclined with respect to the model boundaries.

The free-field model consists of four plane free-field grids on the side boundaries of the model, and four column free-field grids at the corners (see Figure 4). The plane grids are generated to match the main-grid zones on the side boundaries, so that there is a one-to-one correspondence between gridpoints in the free field and the main grid. The four corner free-field columns act as free-field boundaries for the plane free-field grids. The plane free-field grids are two-dimensional calculations that assume infinite extension in the direction normal to the plane. The column free-field grids are one-dimensional calculations that assume infinite extension in both horizontal directions. Both the plane and column grids consist of standard FLAC3D zones, which have gridpoints constrained in such a way as to achieve the infinite extension assumption.

The model should be in static equilibrium before the free-field boundary is applied.

The static equilibrium conditions prior to the dynamic analysis are transferred

to the free field automatically when the zone dynamic free-field command is invoked.

The free-field condition is applied to lateral boundary gridpoints.

All zone data (including model types and current state variables) in the model zones adjacent

to the free field are copied to the free-field region.

Free-field stresses are assigned the average stress of the neighboring grid zone.

The dynamic boundary conditions at the base of the model should be specified before applying the free-field.

These base conditions are automatically transferred to the free field when the free field is applied.

Note that the free field is continuous; if the main grid contains an interface that extends to a model boundary,

the interface will not continue into the free field.

After the zone dynamic free-field command is issued,

the free-field grid will plot automatically whenever the main grid is plotted.

Any model or nonlinear behavior may exist in the free field, as can fluid coupling and flow within the free field.

The following is a link to a simple example of the free-field boundary in use for the model shown in Figure 4.

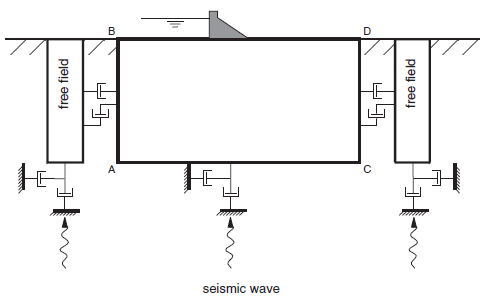

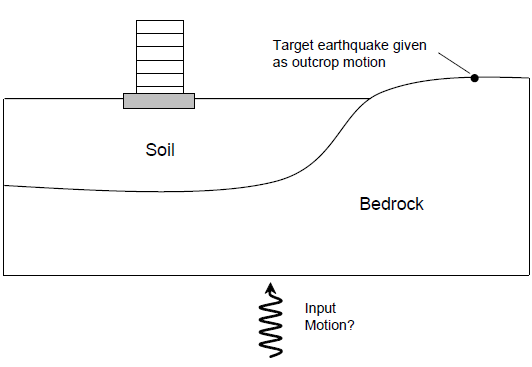

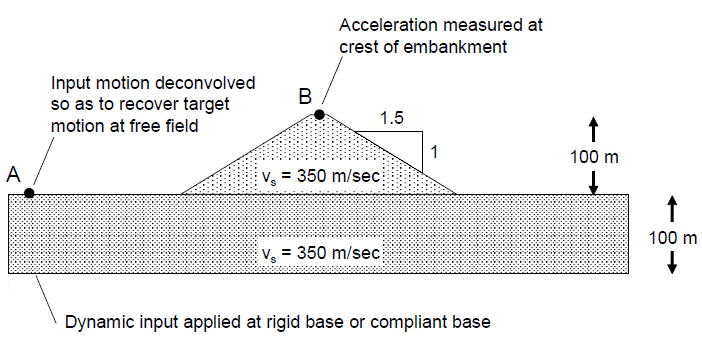

Deconvolution and Selection of Dynamic Boundary Conditions

Design earthquake ground motions developed for seismic analyses are usually provided as outcrop motions, often rock outcrop motions. [1] However, for FLAC3D analyses, seismic input must be applied at the base of the model rather than at the ground surface, as illustrated in Figure 5. The question then arises: “What input motion should be applied at the base of a FLAC3D model in order to properly simulate the design motion?”

The appropriate input motion at depth can be computed through a “deconvolution” analysis using a 1D wave propagation code such as the equivalent-linear program SHAKE. This seemingly simple analysis is often the subject of considerable confusion resulting in improper ground motion input for FLAC3D models. The application of SHAKE for adapting design earthquake motions for FLAC3D input is described. Input of an earthquake motion into FLAC3D is typically done using one of the following:

- A rigid base, where an acceleration-time history is specified at the base of the FLAC3D mesh.

- A compliant base, where a quiet (absorbing) boundary is used at the base of the FLAC3D mesh.

Figure 5: Seismic input to FLAC3D.

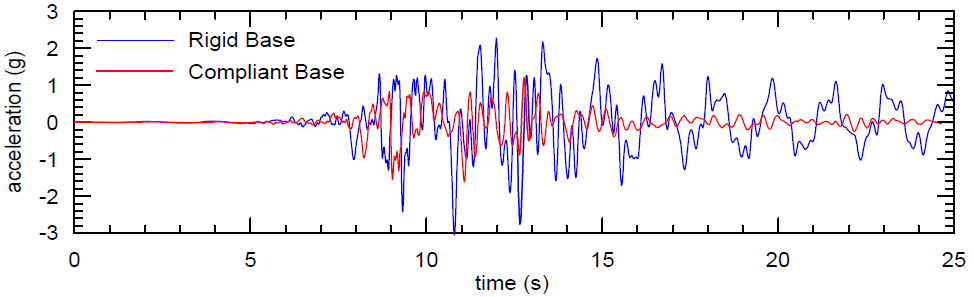

For a rigid base, a time history of acceleration (or velocity or displacement) is specified for gridpoints along the base of the mesh. While simple to use, a potential drawback of a rigid base is that the motion at the base of the model is completely prescribed. Hence, the base acts as if it were a fixed displacement boundary reflecting downward-propagating waves back into the model. Thus, a rigid base is not an appropriate boundary for general application unless a large dynamic impedance contrast is meant to be simulated at the base (e.g., low velocity sediments over high velocity bedrock).

For a compliant base simulation, a quiet boundary is specified along the base of the FLAC3D mesh. See the section on quiet boundaries. Note that if a history of acceleration is recorded at a gridpoint on the quiet base, it will not necessarily match the input history. The input stress-time history specifies the upward-propagating wave motion into the FLAC3D model, but the actual motion at the base will be the superposition of the upward motion and the downward motion reflected back from the FLAC3D model.

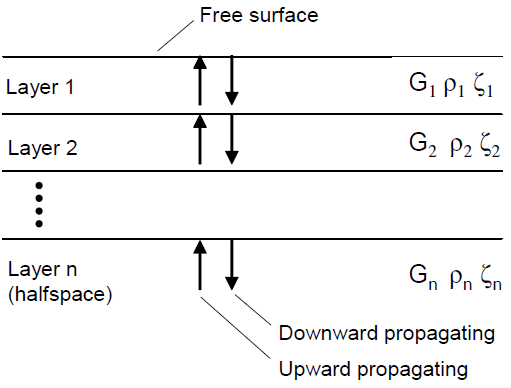

SHAKE (Schnabel et al. 1972) is a widely used 1D wave propagation code for site response analysis. SHAKE computes the vertical propagation of shear waves through a profile of horizontal visco-elastic layers. Within each layer, the solution to the wave equation can be expressed as the sum of an upward-propagating wave train and a downward-propagating wave train. The SHAKE solution is formulated in terms of these upward- and downward-propagating motions within each layer, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Layered system analyzed by SHAKE (layer properties are shear modulus, \(G\), density, \(\rho\) and damping fraction, \(\zeta\)).

The relation between waves in one layer and waves in an adjacent layer can be solved by enforcing the continuity of stresses and displacements at the interface between the layers. These well-known relations for reflected and transmitted waves at the interface between two elastic materials (Kolsky 1963) can be expressed in terms of recursion formulas. In this way, the upward- and downward-propagating motions in one layer can be computed from the upward and downward motions in a neighboring layer.

To satisfy the zero shear stress condition at the free surface, the upward- and downward-propagating motions in the top layer must be equal. Starting at the top layer, repeated use of the recursion formulas allows the determination of a transfer function between the motions in any two layers of the system. Thus, if the motion is specified at one layer in the system, the motion at any other layer can be computed.

SHAKE input and output is not in terms of the upward- and downward-propagating wave trains, but in terms of the motions at a) the boundary between two layers, referred to as a “within” motion, or b) at a free surface, referred to as an “outcrop” motion. The within motion is the superposition of the upward- and downward-propagating wave trains. The outcrop motion is the motion that would occur at a free surface at that location. Hence the outcrop motion is simply twice the upward-propagating wave-train motion. If needed, the upward-propagating motion can be computed by taking half the outcrop motion. At any point, the downward-propagating motion can then be computed by subtracting the upward-propagating motion from the within motion.

The SHAKE solution is in the frequency domain, with conversion to and from the time-domain performed with a Fourier transform. The deconvolution analysis discussed below illustrates the application of SHAKE for a linear, elastic case. See Comparison of FLAC3D to SHAKE for a Layered, Linear-Elastic Soil Deposit. SHAKE can also address nonlinear soil behavior approximately, through the equivalent linear approach. Analyses are run iteratively to obtain shear modulus and damping values for each layer that is compatible with the computed effective strain for the layer. See Comparison of FLAC3D to SHAKE for a Layered, Nonlinear-Elastic Soil.

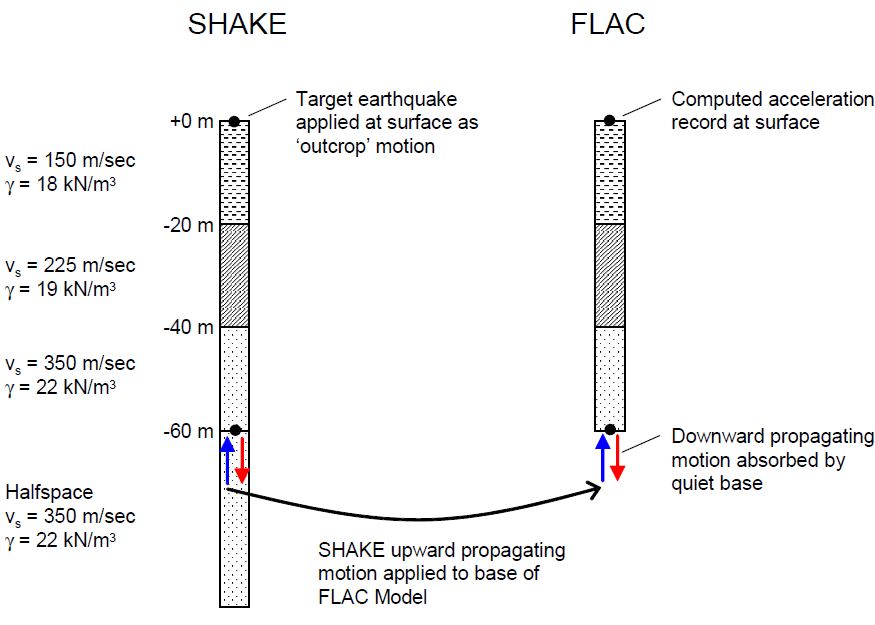

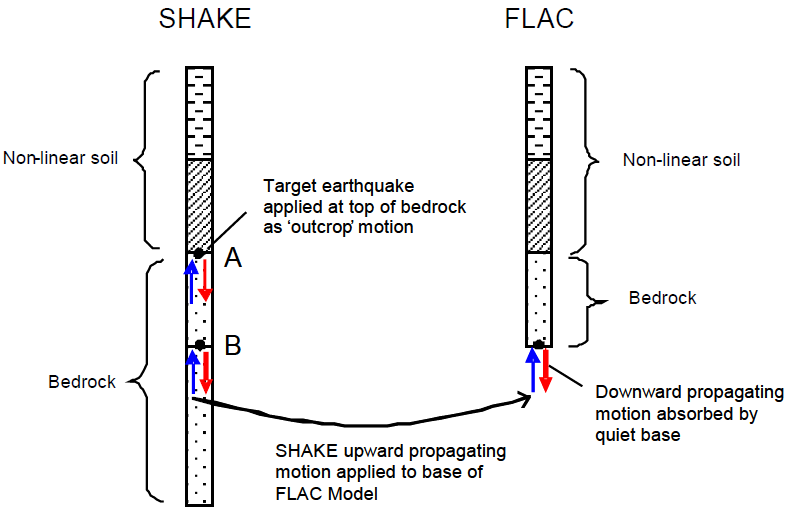

Deconvolution for a Rigid Base — The deconvolution procedure for a rigid base is illustrated in Figure 7 for a two-dimensional FLAC simulation. The same procedure also applies to FLAC3D. The goal is to determine the appropriate base input motion to FLAC such that the target design motion is recovered at the top surface of the FLAC model. The profile modeled consists of three 20-m thick elastic layers with shear wave velocities and densities as shown in the figure. The SHAKE model includes the three elastic layers and an elastic half-space with the same properties as the bottom layer. The FLAC model consists of a column of linear elastic elements. The target earthquake is input at the top of the SHAKE column as an outcrop motion. Then, the motion at the top of the half-space is extracted as a within motion and is applied as an acceleration-time history to the base of the FLAC model. Mejia and Dawson (2006) show that the resulting acceleration at the surface of the FLAC model is virtually identical to the target motion. The SHAKE within motion is appropriate for rigid-base input because, as described above, the within motion is the actual motion at that location, the superposition of the upward- and downward-propagating waves.

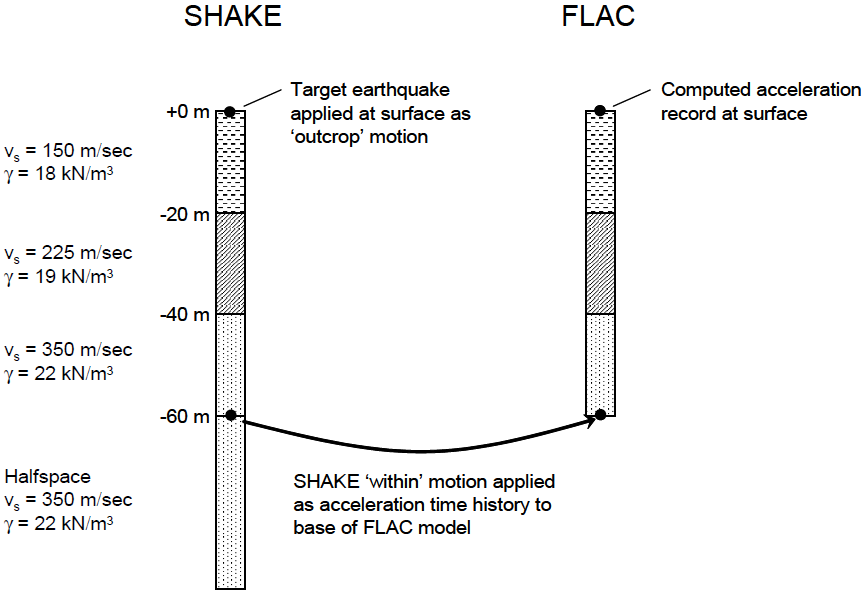

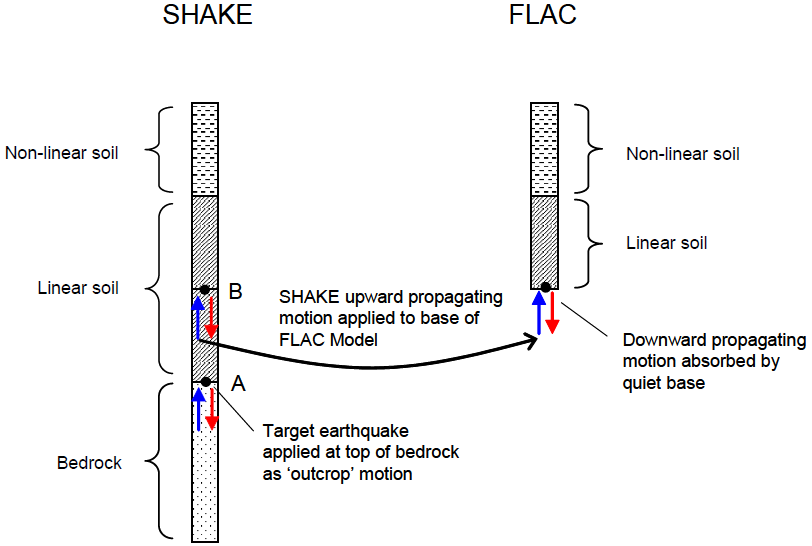

Deconvolution for a Compliant Base — The deconvolution procedure for a compliant base is illustrated in Figure 8 for a FLAC simulation. Again, the same procedure applies to FLAC3D. The SHAKE and FLAC models are identical to those for the rigid body exercise, except that a quiet boundary is applied to the base of the FLAC mesh. For application through a quiet base, the upward-propagating wave motion (1/2 the outcrop motion) is extracted from SHAKE at the top of the half-space. This acceleration-time history is integrated to obtain a velocity, which is then converted to a stress history using Equation (4). Again, the resulting acceleration at the surface of the FLAC model is shown by Mejia and Dawson (2006) to be virtually identical to the target motion. As an additional check of the computed accelerations, they also show that the response spectra for both the compliant-base and rigid-base cases closely match the response spectra of the target motion.

Figure 7: Deconvolution procedure for a rigid base (after Mejia and Dawson 2006).

Figure 8: Deconvolution procedure for a compliant base (after Mejia and Dawson 2006).

Although useful for illustrating the basic ideas behind deconvolution, the previous example is not the typical case encountered in practice. The situation shown in Figure 9, where one or more soil layers (expected to behave nonlinearly) overlay bedrock (assumed to behave linearly), is more common. A FLAC or FLAC3D model for this case will usually include the soil layers and an elastic base of bedrock. To compute the correct FLAC3D compliant base input, a SHAKE model is constructed as shown in the figure. The SHAKE model includes a bedrock layer equal in thickness to the elastic base of the FLAC3D mesh, and an underlying elastic half-space with bedrock properties. The target motion is input to the SHAKE model as an outcrop motion at the top of the bedrock (point A). Designating this motion as outcrop means that the upward-propagating wave motion in the layer directly below point A will be set equal to 1/2 the target motion. The upward-propagating motion for input to FLAC3D is extracted at point B as 1/2 the outcrop motion.

For the compliant-base case, there is actually no need to include the soil layers in the SHAKE model, as these will have no effect on the upward-propagating wave train between points A and B. In fact, for this simple case, it is not really necessary to perform a formal deconvolution analysis, as the upward-propagating motion at point B will be almost identical to that at point A. Apart from an offset in time, the only differences will be due to material damping between the two points, which will generally be small for bedrock. Thus, for this very common situation, the correct input motion for FLAC3D is simply 1/2 of the target motion. (Note that the upward-propagating wave motion must be converted to a stress-time history using Equation (4), which includes a factor of 2 to account for the stress absorbed by the viscous dashpots.)

For a rigid-base analysis, the within motion at point B is required. Since this within motion incorporates downward-propagating waves reflected off the ground surface, the nonlinear soil layers must be included in the SHAKE model. However, soil nonlinearity will be modeled quite differently in FLAC3D and SHAKE. Thus, it is difficult to compute the appropriate FLAC3D input motion for a rigid-base analysis.

Another typical case encountered in practice is illustrated in Figure 10. Here, the soil profile is deep, and rather than extending the FLAC3D mesh all the way down to bedrock, the base of the model ends within the soil profile. Note that the mesh must be extended to a depth below which the soil response is essentially linear. Again, the design motion is input at the top of the bedrock (point A) as an outcrop motion, and the upward-propagating motion for input to FLAC3D is extracted at point B. As in the previous example, for a compliant-base analysis there is no need to include the soil layers above point B in the SHAKE model. These layers have no effect on the upward-propagating motion between points A and B. Unlike the previous case, the upward-propagating motion can be quite different at points A and B, depending on the impedance contrast between the bedrock and linear soil layer. Thus, it is not appropriate to skip the deconvolution analysis and use the target motion directly.

A rigid base is only appropriate for cases with a large impedance contrast at the base of the model. However, the use of SHAKE to compute the required input motion for a rigid base of a FLAC3D model leads to a good match between the target surface motion and the surface motion computed by FLAC3D only for a model that exhibits a low level of nonlinearity. The input motion already contains the effect of all layers above the base, because it contains the downward-propagating wave.

Figure 9: Compliant-base deconvolution procedure for a typical case (after Mejia and Dawson 2006).

Figure 10: Compliant-base deconvolution procedure for another typical case (after Mejia and Dawson 2006).

A different approach must be taken if a FLAC3D model with a rigid base is used to simulate more realistic systems (e.g., sites that exhibit strong nonlinearity, or the effect of a surface or embedded structure). In the first case, the real nonlinear response is not accounted for by SHAKE in its estimate of base motion. In the second case, secondary waves from the structure will be reflected from the rigid base, causing artificial resonance effects.

A compliant base is almost always the preferred option because downward-propagating waves are absorbed. In this case, the quiet-base condition is selected, and only the upward-propagating wave from SHAKE is used to compute the input stress history. By using the upward-propagating wave only at a quiet FLAC3D base, no assumptions need to be made about secondary waves generated by internal nonlinearities or structures within the grid, because the incoming wave is unaffected by these; the outgoing wave is absorbed by the compliant base.

Although the presence of reflections from a rigid base is not always obvious in complex nonlinear FLAC3D analyses, they can have a major impact on analysis results, especially when cyclic-degradation or liquefaction-soil models are employed. Mejia and Dawson (2006) present examples from two-dimensional FLAC simulations that illustrate the nonphysical wave reflections calculated in models with a rigid base. One example, shown in Figure 11, demonstrates the difficulty with a rigid boundary. The nonphysical oscillations that result from a rigid base are shown by comparison to results for a compliant base in Figure 12. The inputs in both cases (rigid and compliant) were derived by deconvoluting the same surface motion.

Figure 11: Embankment analyzed with a rigid and compliant base (after Mejia and Dawson 2006).

Hydrodynamic Pressures

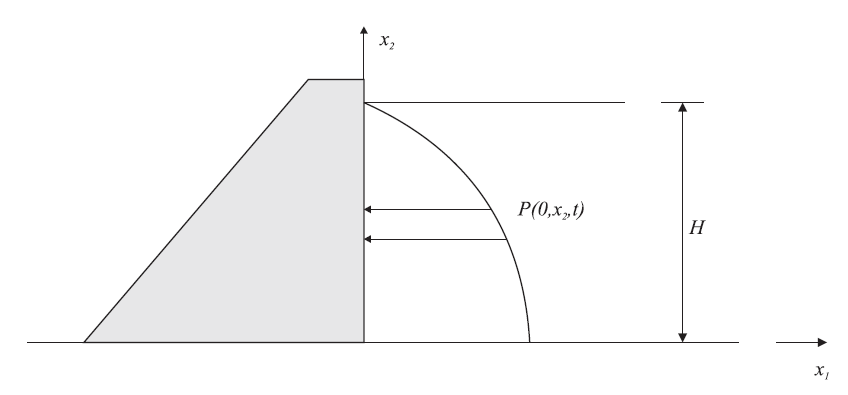

The dynamic interaction between water in a reservoir and a concrete dam can have a significant influence on the performance of the dam during an earthquake. Westergaard (1933) established a mathematical basis for procedures to represent this interaction, and this approach is commonly used in engineering practice. Although the advent of computers has enabled numerical solution of coupled differential equations of fluid-structure systems, the formula proposed by Westergaard is widely used for stability analysis of smaller dams and preliminary calculations in the design of large dams.

Figure 13: Hydrodynamic pressure acting on a rigid dam with a vertical upstream face.

The hydrodynamic pressure acting on a rigid concrete dam over a reservoir height, \(H\), is depicted in Figure 13. The pressure can be derived from the equation of motion for a fluid. The equation of motion for a fluid with small Reynold’s number can be written as

where \(c\) is the speed of sound in water and \(\Phi\) is the velocity potential. The water pressure can be written as a function of the velocity potential:

where \(\rho_w\) is the density of water.

Additional assumptions are made to simplify the loading condition:

- The water is assumed to be incompressible, which reduces Equation (10) to the Laplace equation: \(\frac{\delta^2 \Phi}{\delta x_1^2} + \frac{\delta^2 \Phi}{\delta x_2^2} = 0\).

- The free surface of the reservoir is assumed to be at rest. Thus, \(\frac{\delta \Phi}{\delta t} = 0\) at \(x_2 = H\).

- The reservoir is assumed to be infinitely long. Therefore, as \(x_1 \rightarrow \infty, \Phi \rightarrow 0\).

- Hydrodynamic motion is assumed to be horizontal only: \(\frac{\delta \Phi}{x_2} = 0\) at \(x_2 = 0\).

- The upstream face of the dam is vertical and the dam is rigid: \(\frac{\delta \Phi}{x_1} = f(t)\) at \(x_1 = 0\).

The solution of Equation (10) with the preceding assumptions can be obtained for an arbitrary acceleration, \(\ddot{x}_0 (t)\), in the form of an infinite Fourier series:

Equation (11) can be approximated as

where \(C_m\) = 0.743 and \(\ddot{x}\) is the horizontal acceleration at the dam face.

Equation (12) is implemented in FLAC3D by adjusting the grid point mass on the upstream face of the dam to account for the hydrodynamic pressure. The equivalent pressure, \(\bar{p}\), resulting from the inertial forces associated with the gridpoint and the hydrodynamic pressure of the water in the reservoir, averaged over the area associated with the gridpoint, can be written as

where \(A_g\) is the area associated with the gridpoint, \(\Delta x_2\) is the contact length on the upstream face of the dam through which the water load is applied for the gridpoint, and \(\rho_ec\) is the equivalent density of the gridpoint and is given by

where

\(\rho_c\) is the density of concrete such that the gridpoint mass is given by \(m_g = A_g \rho_c\). The scaled gridpoint mass, \(m_sg = A_g \rho_ec\), is used only for the motion calculation in the horizontal direction; the effect of the increase mass does not influence the vertical forces.

The gridpoint mass is adjusted by adding the term (as determined by Equation

(13)) to account for the hydrodynamic pressure. This adjustment is stored in

a location that is modifiable using the FISH gridpoint function gp.mass.add.

The conditions are applied using the zone face westergaard command.

The following simple example is provided that illustrates the effect of hydrodynamic pressures and compares the Westergaard approximation to the result of explicitly modeling the water using FLAC3D zones.

Wave Transmission

Accurate Wave Propagation

Numerical distortion of the propagating wave can occur in a dynamic analysis as a function of the modeling conditions. Both the frequency content of the input wave and the wave speed characteristics of the system will affect the numerical accuracy of wave transmission. Kuhlemeyer and Lysmer (1973) show that, for accurate representation of wave transmission through a model, the spatial element size, \(\Delta l\), must be smaller than approximately one-tenth to one-eighth of the wavelength associated with the highest frequency component of the input wave. For instance,

where \(\lambda\) is the wavelength associated with the highest frequency component that contains appreciable energy.

Filtering

For dynamic input with a high peak velocity and short rise time, the Kuhlemeyer and Lysmer requirement may necessitate a very fine spatial mesh and a corresponding small timestep. The consequence is that reasonable analyses may be prohibitively time- and memory-consuming. In such cases, it may be possible to adjust the input by recognizing that most of the power for the input history is contained in lower-frequency components (e.g., use “fft.fis” in “datafiles\FISH\Library”). By filtering the history and removing high frequency components, a coarser mesh may be used without significantly affecting the results.

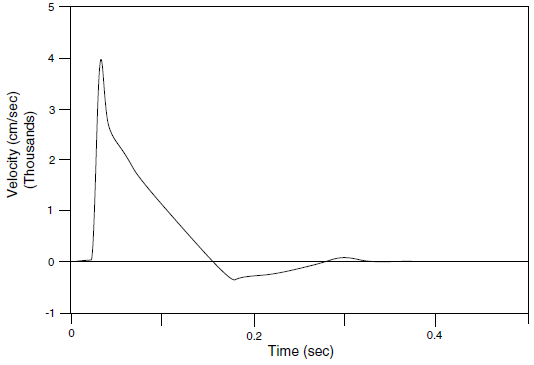

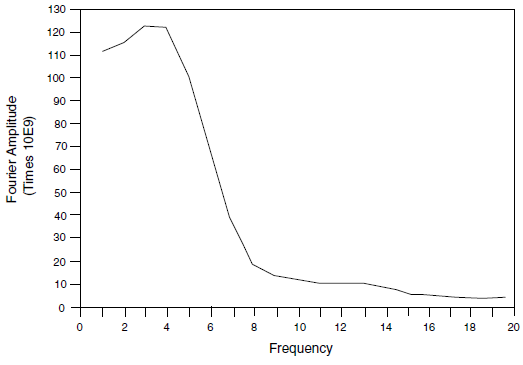

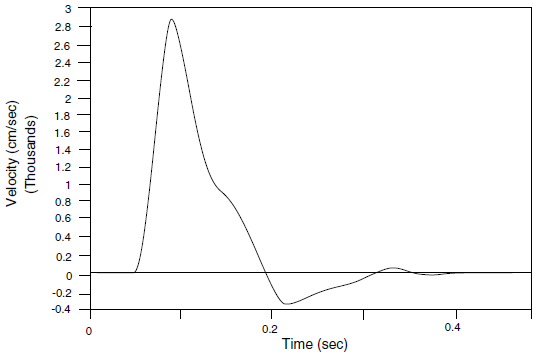

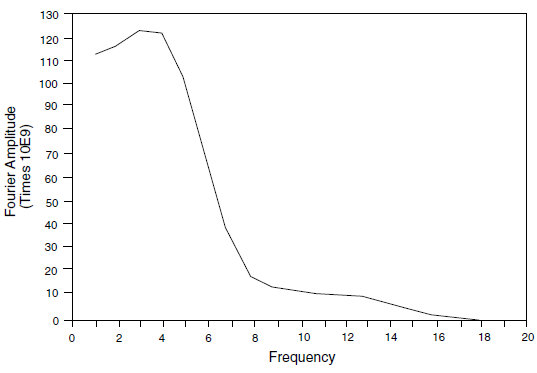

The filtering procedure can be accomplished with a low-pass filter routine such as the fast Fourier transform technique. For example, the unfiltered velocity record shown in Figure 14 represents a typical waveform containing a very high frequency spike. The highest frequency of this input exceeds 50 Hz but, as shown by the power spectral density plot of Fourier amplitude versus frequency (Figure 15), most of the power (approximately 99%) is made up of components of frequency 15 Hz or lower. It can be inferred, therefore, that by filtering this velocity history with a 15 Hz low-pass filter, less than 1% of the power is lost. The input filtered at 15 Hz is shown in Figure 16, and the Fourier amplitudes are plotted in Figure 17. The difference in power between unfiltered and filtered input is less than 1%, while the peak velocity is reduced 38%, and the rise time is shifted from 0.035 to 0.09 seconds. Analyses should be performed with input at different levels of filtering to evaluate the influence of the filter on model results.

If a simulation is run with an input history that violates Equation (14), the output will contain spurious “ringing” (superimposed oscillations) that are nonphysical. The input spectrum must be filtered before being applied to a FLAC3D grid. This limitation applies to all numerical models in which a continuum is discretized; it is not just a characteristic of FLAC3D. Any discretized medium has an upper limit to the frequencies that it can transmit, and this limit must be respected for the results to be meaningful. Users of time-domain codes commonly apply sharp pulses or step waveforms to the numerical grid; this is not acceptable, since these waveforms have spectra that extend to infinity. It is a simple matter to apply, instead, a smooth pulse that has a limited spectrum. Alternatively, artificial viscosity may be used to spread sharp wave-fronts over several zones (see Artificial Viscosity), but this method strictly only applies to isotropic strain components.

Figure 14: Unfiltered velocity history.

Figure 15: Unfiltered power spectral density plot.

Figure 16: Filtered velocity history at 15 Hz.

Figure 17: Results of filtering at 15 Hz.

Mechanical Damping and Material Response

Natural dynamic systems contain some degree of damping of the vibration energy within the system; otherwise, the system would oscillate indefinitely when subjected to driving forces. Damping is due, in part, to energy loss as a result of internal friction in the intact material and slippage along interfaces, if these are present.

FLAC3D uses a dynamic algorithm for solution of two general classes of mechanical problems: quasi-static and dynamic. Damping is used in the solution of both classes of problems, but quasi-static problems require more damping for rapid convergence to equilibrium. The damping for static solutions is discussed in Mechanical Damping.

For a dynamic analysis, the damping in the numerical simulation should reproduce, in magnitude and form, the energy losses in the natural system when subjected to a dynamic loading. In soil and rock, natural damping is mainly hysteretic (i.e., independent of frequency—see Gemant and Jackson 1937, and Wegel and Walther 1935). It is difficult to reproduce this type of damping numerically because of at least two problems (see Cundall 1976, and comments in Characteristics of Fully Nonlinear Method). First, many simple hysteretic functions do not damp all components equally when several waveforms are superimposed. Second, hysteretic functions lead to path-dependence, which makes results difficult to interpret. However, if a constitutive model that contains an adequate representation of the hysteresis that occurs in a real material is found, then no additional damping would be necessary. This comment is addressed to users who program their own constitutive models in C++; the built-in models are not considered to model dynamic hysteresis well enough to omit additional damping completely.

For several reasons, it is impractical to use the “real” stress/strain response of the material in numerical simulations. For example: 1) there are no laws that describe the complete material response; and 2) existing laws that capture many important aspects have many material parameters requiring extensive calibration.

In time-domain programs, Rayleigh damping is commonly used to provide damping that is approximately frequency-independent over a restricted range of frequencies. Although Rayleigh damping embodies two viscous elements (in which the absorbed energy is dependent on frequency), the frequency-dependent effects are arranged to cancel out at the frequencies of interest.

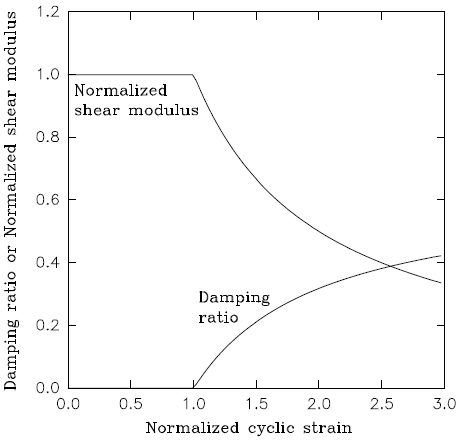

Hysteretic damping is an alternative damping option. This form of damping allows strain-dependent modulus and damping functions to be incorporated directly into the FLAC3D simulation. This makes it possible to make direct comparisons between calculations made with the equivalent-linear method and a fully nonlinear method, without making any compromises in the choice of constitutive model.

For routine engineering design, we must use an approximate representation of cyclic energy dissipation. In FLAC3D, when using simple plasticity models such as Mohr-Coulomb, the choice is between Rayleigh damping and hysteretic damping. Here, we make some general comparisons between the two approaches, enabling a choice to be made. In general, hysteretic damping is the more realistic of the two, and it entails no reduction in timestep. For further discussion, see Integration of Damping Schemes and Nonlinear Material Models for Geo-materials.

For low levels of cyclic strain and fairly uniform conditions, Rayleigh damping and hysteretic damping give similar results, provided that the levels of damping set for both are consistent with the levels of cyclic strain experienced. The results will differ in the following two circumstances:

1. When the system is nonuniform (e.g., layers of quite different properties), then cyclic strain levels may be different in different locations and at different times. Using hysteretic damping, these different strain levels produce realistically different damping levels in time and space, while constant and uniform Rayleigh damping parameters can only reproduce the average response. It would be possible to adjust the Rayleigh damping parameters to account for spatial variations in damping using an iterative (strain-compatible) scheme, as used in the equivalent-linear method. It may also be possible to adjust the Rayleigh damping parameters in time, although some practical difficulties may be encountered.

2. As yield is approached, neither Rayleigh damping nor hysteretic damping account for the energy dissipation of extensive yielding. Thus, irreversible strain occurs externally to both schemes, and dissipation is represented by the yield model (e.g., Mohr-Coulomb). Under this condition, the mass-proportional term of Rayleigh damping may inhibit yielding because rigid-body motions that occur during failure modes are erroneously resisted. Hysteretic damping may give rise to larger permanent strains in such a situation, but this condition is usually believed to be more realistic compared to one using Rayleigh damping.

We note that hysteretic damping provides almost no energy dissipation at very low cyclic strain levels, which may be unrealistic. To avoid low-level oscillation, it is recommended that a small amount (e.g., 0.2%) of stiffness-proportional Rayleigh damping be added when hysteretic damping is used in a dynamic simulation.

Another form of damping in FLAC3D, the local damping embodied in FLAC3D’s static solution scheme, may be used dynamically, but with a damping coefficient appropriate to wave propagation. Local damping in dynamic problems is useful as an approximate way to include hysteretic damping. However, it becomes increasingly unrealistic as the complexity of the waveforms increases (i.e., as the number of frequency components increases). Local damping cannot properly capture the energy loss of multiple frequency cyclic loading.

A fourth form of damping, artificial viscosity, is also provided in FLAC3D. This damping may be used for analyses involving sharp dynamic fronts.

Rayleigh Damping

Rayleigh damping was originally used in the analysis of structures and elastic continua to damp the natural oscillation modes of the system. The equations, therefore, are expressed in matrix form.

A damping matrix, \(C\), is used with components proportional to the mass, \(M\), and stiffness, \(K\), matrices:

where \(\alpha\) is the mass-proportional damping constant; and \(\beta\) is the stiffness-proportional damping constant.

The mass-proportional term is analogous to a dashpot connecting every FLAC3D gridpoint to “ground.” The stiffness-proportional term is analogous to a dashpot connected across each FLAC3D zone (responding to the strain rate). Although both terms are frequency-dependent, an approximately frequency-independent response can be obtained over a limited frequency range with the appropriate choice of parameters as discussed below.

For a multiple degree-of-freedom system, the critical damping ratio, \(\xi_i\), at any angular frequency of the system, \(\omega_i\), can be found from (Bathe and Wilson 1976)

or

The critical damping ratio, \(\xi_i\), is also known as the fraction of critical damping for mode \(i\) with angular frequency \(\omega_i\).

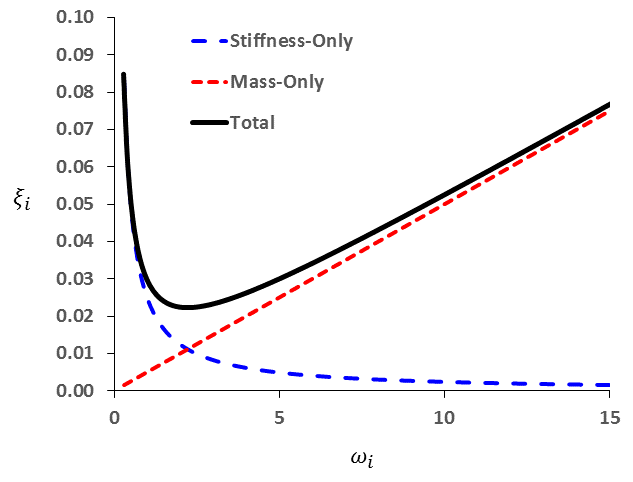

Figure 18 shows the variation of the normalized critical damping ratio with angular frequency \(\omega_i\). Three curves are given: mass components only; stiffness components only; and the sum of both components. As shown, mass-proportional damping is dominant at lower angular-frequency ranges, while stiffness-proportional damping dominates at higher angular frequencies. The curve representing the sum of both components reaches a minimum at

or

The center frequency is then defined as

Note that at frequency \(\omega_{\min}\) (or \(f_{\min}\)) (and only at that frequency), mass damping, and stiffness damping each supply half of the total damping force.

Figure 18: Variation of normalized critical damping ratio with angular frequency.

Rayleigh damping is specified in FLAC3D with the parameters \(f_{\min}\)

in Hertz (cycles per second) and \(\xi_{\min}\), both specified with the

zone dynamic damping rayleigh command.

Stiffness-proportional damping causes a reduction in the critical timestep for the explicit solution scheme (see Belytschko 1983). As the damping ratio corresponding to the highest natural frequency is increased, the timestep is reduced (see Dynamic Timestep). This can result in a substantial increase in runtimes for dynamic simulations.

In FLAC3D, the internal timestep calculation takes account of stiffness-proportional

damping, but it is still possible for instability to occur if the large-strain calculation

is in effect (model largestrain) and very large mesh deformation occurs.

If this happens, it is necessary to reduce the timestep manually (via the

model dynamic timestep fix command).

For the case shown in Figure 18, \(\omega_{\min} = 10\) radians per second. It is evident that the damping ratio is almost constant over at least a 3:1 frequency range (e.g., from 5 to 15). Since damping in geologic media is commonly independent of frequency (as discussed in Dynamic Mechanical Damping), \(\omega_{\min}\) is usually chosen to lie in the center of the range of frequencies present in the numerical simulation — either natural frequencies of the model or predominant input frequencies. Hysteretic damping is thereby simulated in an approximate fashion.

Viscous stress increments representing the stiffness-proportional component of Rayleigh damping are added to the total stress increments during a timestep in order to compute gridpoint forces. Thus,

where \(\sigma_v\) is a component of the combined stress tensor used to derive gridpoint forces, \(\sigma_n\) is the corresponding component returned from the constitutive law, and \(\sigma_o\) is the value of the component prior to invoking the constitutive law. The notation \(\bigl\{\) \(\bigr\}\) denotes the vector of all components.

Viscous stresses are not included with the accumulated total stresses (\(\sigma_n\)).

A stiffness matrix is not needed in this formulation. Rayleigh damping operates directly on the tangent modulus for the constitutive model, whether it is linear or nonlinear.

Stiffness-proportional damping is turned off when plastic failure occurs within a FLAC3D

zone. Mass-proportional damping, however, remains active. If excessive failure occurs in a

model, the mass-proportional term may inhibit yielding. In this case, it may be advisable to

exclude Rayleigh damping from regions of strong plastic flow (by using the

zone dynamic damping rayleigh command to set Rayleigh damping in selected regions,

as described in Spatial Variation in Damping).

Example Application of Rayleigh Damping

In order to demonstrate how Rayleigh damping works in FLAC3D, the following simple example examines the results of four damping cases for comparison.

Guidelines for Selecting Rayleigh Damping Parameters

Damping Ratio, \(\xi_{\min}\)

What is normally attempted in a dynamic analysis is the reproduction of the frequency-independent damping of materials at the correct level. For geological materials, damping commonly falls in the range of 2 to 5% of critical; for structural systems, 2 to 10% is representative (Biggs 1964). Also, see Newmark and Hall (1982) for recommended damping values for different materials. In analyses that use one of the plasticity constitutive models (e.g., Mohr-Coulomb), a considerable amount of energy dissipation can occur during plastic flow. Thus, for many dynamic analyses that involve large-strain, only a minimal percentage of damping (e.g., 0.5%) may be required. Further, dissipation will increase with amplitude for stress/strain cycles that involve plastic flow. \(\xi_{\min}\) is adjusted to coincide with the correct physical damping ratio.

The equivalent-linear program SHAKE (Schnabel, Lysmer, and Seed 1972) can be used to estimate material damping to represent the inelastic cyclic behavior of soils. An equivalent-linear analysis is performed for a layered soil deposit using the shear wave speeds and densities for the different layers. Strain-compatible values for the damping ratios and shear-modulus reduction factors are then determined. Average damping ratios and shear modulus reduction factors are estimated for each layer; the damping ratios are the estimates for input in the Rayleigh damping in FLAC3D.

Center Frequency, \(f_{\min}\)

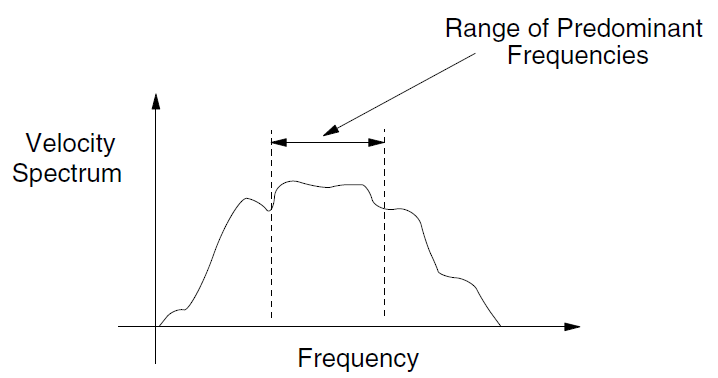

Rayleigh damping is frequency-dependent but has a “flat” region that spans about a 3:1 frequency range, as shown in Figure 18. For any particular problem, a spectral analysis of typical velocity records might produce a response such as the one shown in Figure 19. [2]

Figure 19: Plot of velocity spectrum versus frequency.

If the highest predominant frequency is three times greater than the lowest predominant frequency, then there is a 3:1 span or range that contains most of the dynamic energy in the spectrum. The idea in dynamic analysis is to adjust \(f_{\min}\) of the Rayleigh damping so that its 3:1 range coincides with the range of predominant frequencies in the problem. The predominant frequencies are neither the input frequencies nor the natural modes of the system, but a combination of both. The idea is to try to get the right damping for the important frequencies in the problem.

For many problems, the important frequencies are related to the natural mode of oscillation of the system. Examples of this type of problem include seismic analysis of surface structures such as dams, or dynamic analysis of underground excavations. The fundamental frequency, \(f\), associated with the natural mode of oscillation of a system is

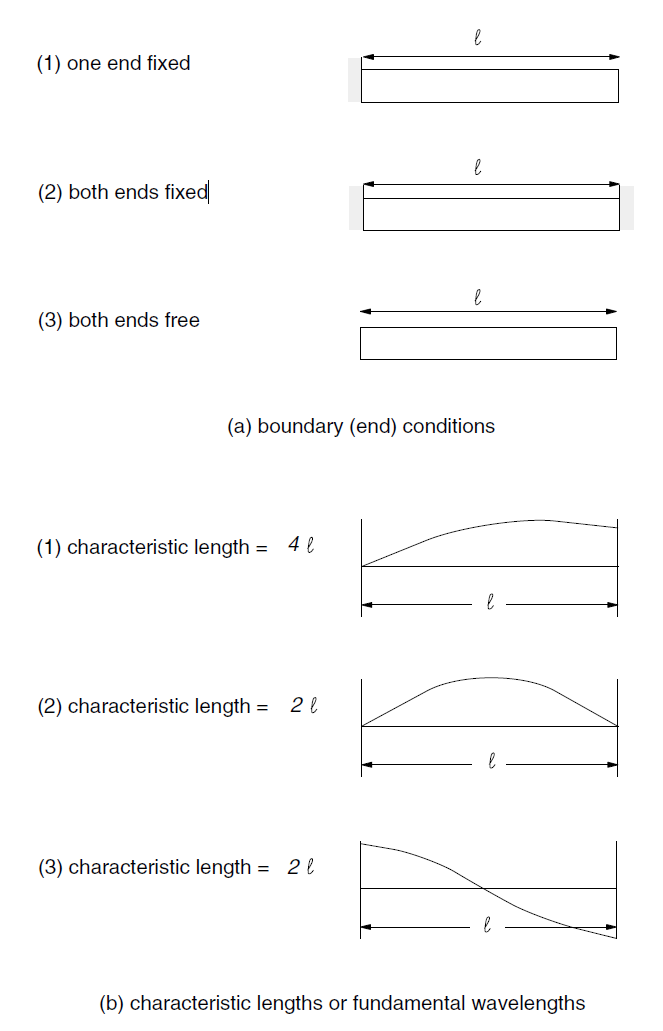

where \(C\) is the speed of propagation associated with the mode of oscillation, and \(\lambda\) is the longest wavelength associated with the mode of oscillation.

For a continuous, elastic system (e.g., a one-dimensional elastic bar), the speed of propagation, \(C_p\), for \(p\)-waves is given by Equation (3), and for \(s\)-waves by Equation (4). If shear motion of the bar gives rise to the lowest natural mode, then \(C_s\) is used in the above equation; otherwise, \(C_p\) is used if motion parallel to the axis of the bar gives rise to the lowest natural mode.

The longest wavelength (or characteristic length or fundamental wavelength) depends on boundary conditions. Consider a solid bar of unit length with boundary conditions as shown in Figure 20a. The fundamental mode shapes for cases (1), (2), and (3) are as shown in Figure 20b. If a wavelength for the fundamental mode of a particular system cannot be estimated in this way, then a preliminary run may be made with zero damping (for example, see Mechanical Damping). A representative natural period may be estimated from time histories of velocity or displacement. Natural Periods of an Elastic Column contains a simple example in which natural periods are estimated by undamped simulations.

Figure 20: Comparison of fundamental wavelengths for bars with varying end conditions.

Hysteretic Damping

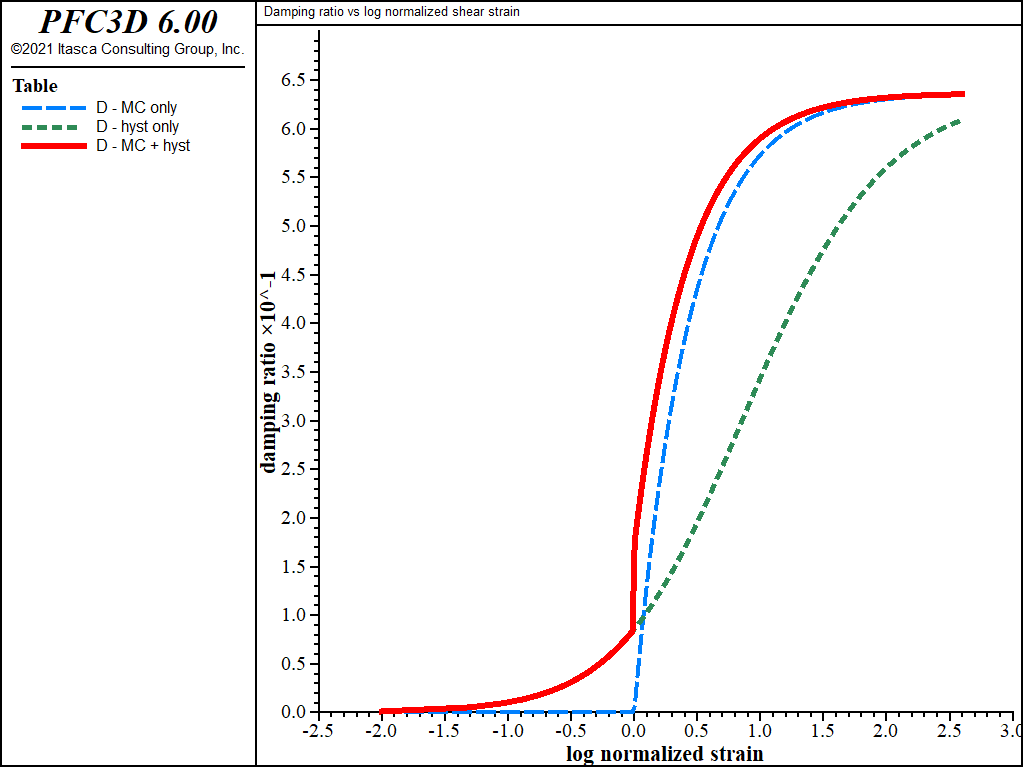

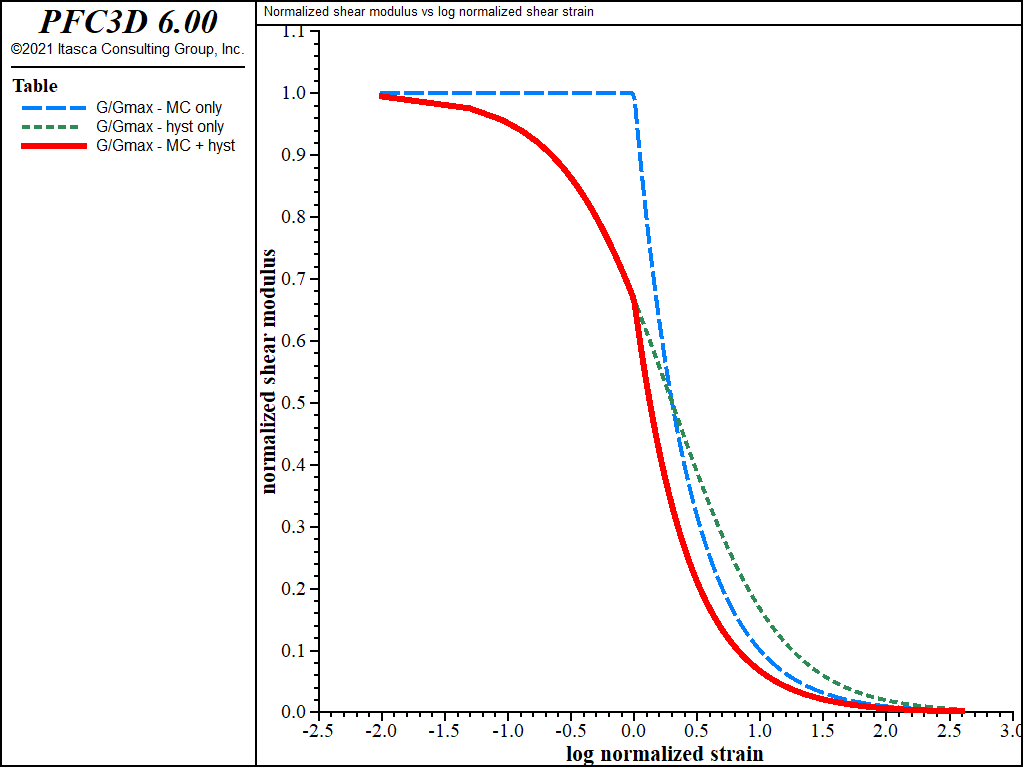

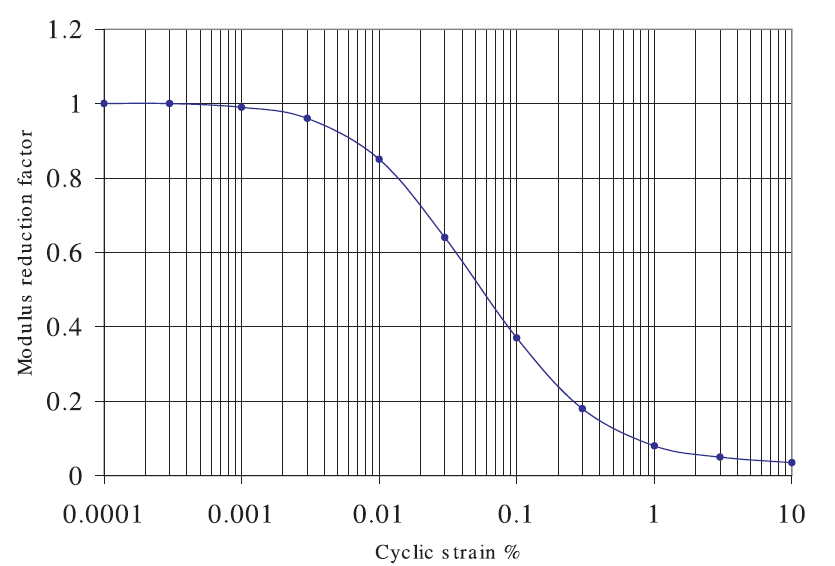

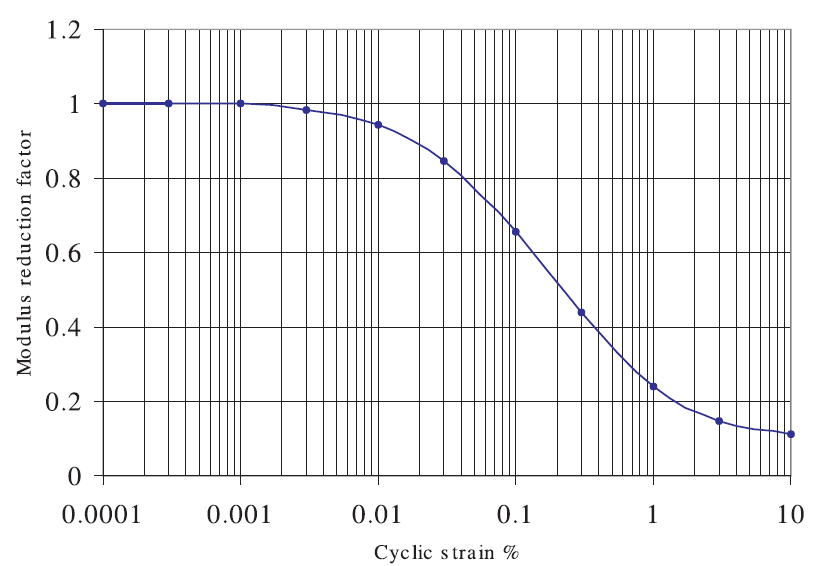

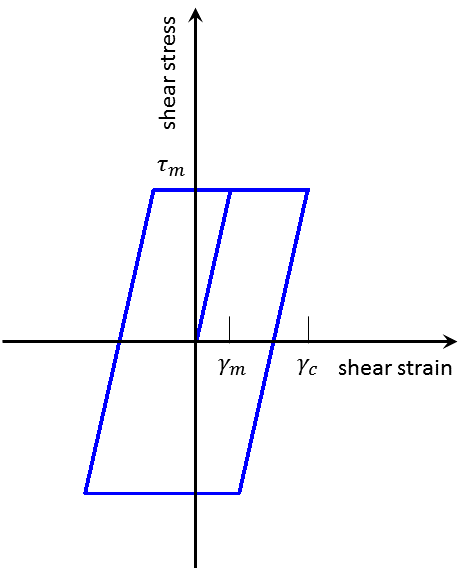

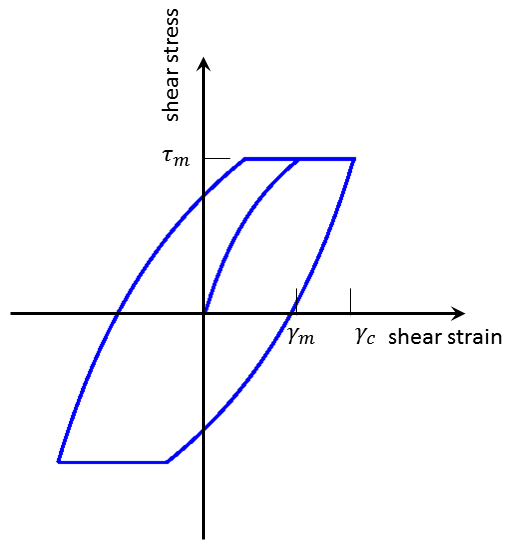

The equivalent-linear method has been in use for many years to calculate the wave propagation (and response spectra) in soil and rock at sites subjected to seismic excitation. The method does not directly capture any nonlinear effects because it assumes linearity during the solution process; strain-dependent modulus and damping functions are only taken into account in an average sense in order to approximate some effects of nonlinearity (damping and material softening). Although fully nonlinear codes such as FLAC3D are capable—in principle—of modeling the correct physics, it has been difficult to convince designers and licensing authorities to accept fully nonlinear simulations. One reason is that the constitutive models available to FLAC3D are either too simple (e.g., an elastic/plastic model, which does not reproduce the continuous yielding seen in soils), or too complicated (e.g., the Wang model [Wang et al. 2001], which needs many parameters and a lengthy calibration process). Further, there is a need to directly accept the same degradation curves used by equivalent-linear methods (see Figure 21 and 22 for examples), to allow engineers to move easily from using these methods to using fully nonlinear methods.

A further motivation for incorporating such cyclic data into a hysteretic damping model for FLAC3D is that the need for additional damping such as Rayleigh damping would be eliminated. Rayleigh damping is unpopular with code users because it often involves a drastic reduction in timestep, and a consequent increase in solution time.

Optional hysteretic damping is described here; it may be used on its own or in conjunction with the other damping schemes, such as Rayleigh damping or local damping. (It may also be used with some of the built-in constitutive models except for the models with nonlinear elastic moduli, e.g., modified Cam-Clay.)

The hysteretic damping formulation is not intended to be a complete constitutive model: it should be used as a supplement to one of the built-in nonlinear models, and not as a primary way to simulate yielding. If models that embody both plastic yield and an adequate hysteretic response are used, then there is no reason to add further damping; the hysteretic damping option in FLAC3D is only intended to provide damping for those models lacking intrinsic damping when not yielding. Further, Rayleigh damping should be unnecessary when hysteretic damping is in operation, apart from its possible use (at low levels: e.g., 0.2%) to remove high frequency noise.

Figure 21: Modulus reduction curve for sand (Seed & Idriss 1970 — “upper range”). The data set is from the file supplied with the SHAKE-91 code download. (https://nisee.berkeley.edu/elibrary/getpkg?id=SHAKE91)

Figure 22: Modulus reduction curve for clay (Sun et al. 1988 — “upper range”). The data set is from the file supplied with the SHAKE-91 code download. (https://nisee.berkeley.edu/elibrary/getpkg?id=SHAKE91)

Hysteretic Damping Formulation, Implementation, and Calibration

Formulation

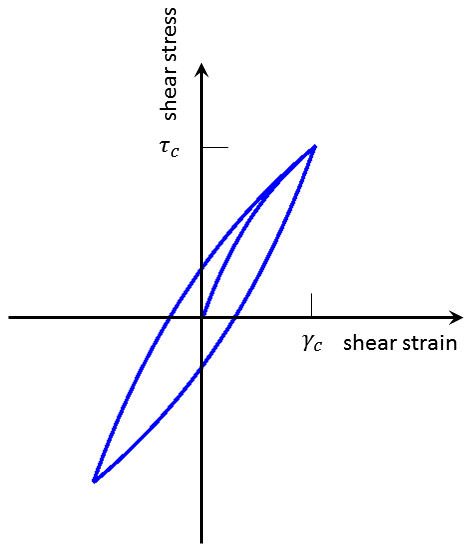

Modulus degradation curves, as illustrated in Figures 21 and 22, imply a nonlinear stress/strain curve. If we assume an ideal soil, in which the stress depends only on the strain (not on the number of cycles, or time), we can derive an incremental constitutive relation from the degradation curve, described by \(\bar {\tau} / \gamma = M_s\), where \(\bar {\tau}\) is the normalized shear stress, \(\gamma\) is the shear strain, and \(M_s\) is the normalized secant modulus.

where \(M_t\) is the normalized tangent modulus. The incremental shear modulus in a nonlinear simulation is then given by \(G_o M_t\). This is used in place of the given shear modulus, \(G_o\) (i.e., the property assigned with the name shear).

In order to handle two- and three-dimensional strain paths, an approach similar to the one described for the Finn model (see Simple Model Formulations) is used, whereby the shear strain is decomposed into components in strain space, and strain reversals are detected by changes in signs of the dot product of the current increment and the previous mean path. Following the formulation of the Finn model (replacing \(\epsilon\) with \(\gamma\) but otherwise using the same notation):

A reversal is detected when \(|d|\) passes through a maximum, and the previous-reversal strain values are updated as given by Equations (37) and (38). Note that there is no “latency” period, as used in the Finn model (see Simple Model Formulations); there is no minimum number of timesteps that must occur before a reversal is detected.

Between reversals, the shear modulus is multiplied by \(M_t\), using \(\gamma = |d|\) in Equation (26). The multiplier is applied to the shear modulus used in all built-in constitutive models, except for the transversely isotropic elastic, modified Cam-clay, and creep material models.

Implementation

The formulation described above is implemented in FLAC3D, by modifying the strain-rate calculation so that the mean strain-rate tensor (averaged over all subzones) is calculated before any calls are made to constitutive model functions. At this stage, the hysteretic logic is invoked, returning a modulus multiplier, which is passed to any called constitutive model. The model then uses the multiplier \(M_t\) to adjust the apparent value of tangent shear modulus of the full zone being processed.

In addition to the “backbone curve,’’ provided by applying Equation (26) to a modulus degradation curve (described below), two Masing (1926) rules are used to specify the behavior at reversal points. Essentially, these state that: 1) a new (but inverted) function is started upon reversal, implying that the initial unload modulus is \(G\); and 2) the first quarter-cycle of loading is scaled by one-half relative to all other cycles. Although Pyke (2004) concludes that “neither of the Masing rules is valid,” some simplifying assumption is necessary to ensure repeatable, closed loops. The fact that real soil departs from this ideal behavior is not believed to be too important in this context because the formulation is not intended to be a complete constitutive model, but simply to provide hysteretic damping as an alternative to Rayleigh damping.

An additional rule deals with sub-cycles: the hysteretic logic contains push-down FILO (first in, last out) stacks that record all state information (e.g., stress, strain, tangent modulus, and previous reversal point) at the point of reversal, for both positive—and negative—going strain directions. If the strain level returns to—and exceeds—a previous value recorded in the stack (of the appropriate sign), the state information is popped from the stack, so that the behavior (and, hence, tangent multiplier) reverts back to that which was applied at the time before the reversal.

The operation of these various rules in illustrated in the following simple example:

The degradation curves used in earthquake engineering are usually given as tables of values, with cyclic strains spaced logarithmically. Since the derivative of the modulus-reduction curve is required here (i.e., for Equation (26)), the coarse spacing (e.g., 11 points in the curve shown in Figure 22) leads to unacceptable errors if numerical derivatives are calculated. Thus, the implemented hysteretic model uses only continuous functions to represent the modulus-reduction curve, so that analytical derivatives may be calculated. The various implemented functions are described in the following section. If degradation curves are available only in table form, they must be fitted to one of the built-in functional forms before simulations can be performed.

The hysteretic damping feature is invoked with the command

zone dynamic damping hysteretic name <v1 v2 v3 …> <range>

where name is the name of the fitting function (chosen from default, sig3, sig4, and hardin — see the following discussion), and v1, v2, v3, …, are numerical values for function parameters. The optional range may be any acceptable range phrase for zones.

Hysteretic damping may be removed from any range of zones with the command

zone dynamic damping hysteretic off <range>

Note that the zone dynamic damping hysteretic command only applies where the

model configure dynamic mode of operation has been selected and when

model configure dynamic applies. Hysteretic damping operates independent of all other

forms of damping, which may be also specified to operate “in parallel” with hysteretic

damping.

Tangent-Modulus Functions

Various built-in functions are available to represent the variation of the shear modulus

reduction factor, \(G/G_{\rm max}\), with cyclic strain (given in percent),

according to the keyword specified on the zone dynamic damping hysteretic command.

Default model — default

The default hysteresis model is developed by noting that the S-shaped curve of modulus versus logarithm of cyclic strain can be represented by a cubic equation, with zero slope at both low strain and high strain. Thus, the secant modulus \(M_s\) is

where

and \(L\) is the logarithmic strain,

The parameters \(L_1\) and \(L_2\) are the extreme values of logarithmic strain (i.e., the values at which the tangent slope becomes zero). Thus, giving \(L_1 = -3\) and \(L_2 = 1\) means that the S-shaped curve will extend from a lower cyclic strain of 0.001% (10-3) to an upper cyclic strain of 10% (101). Since the slopes are zero at these limits, it is not meaningful to operate the damping model with strains outside the limits. (Note that Equation (39) is only assumed to apply for \(0 \leq s \leq 1\), and that the tangent modulus will be set to zero otherwise.) The tangent modulus is given by

Using the chain rule,

we obtain

There is a further limit, \(s > s_{\rm min}\), such that the tangent modulus is always positive (no strain softening). Thus,

or

where \(A = 6 {\rm log}_{10}e / (L_2 - L_1)\). The lowest positive root is

In applying the model, \(M_t = 0$ if $s < s_{\rm min}\).

The default model function can be fit to degradation curves by using a curve-fitting graphing software (e.g., SigmaPlot, http://www.systat.com/products/sigmaplot/ ). For example, the numerical best-fit of the default model to the curves of Figures 21 and 22 are listed in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Sigmoidal models — sig3, sig4

Sigmoidal curves are monotonic within the defined range and have the appropriate asymptotic behavior. Thus the functions are well-suited to represent modulus degradation curves. The two types of sigmoidal model (3 and 4 parameters, respectively) are

sig3 model

sig4 model

The command line for invoking these models requires that three symbols, \(a\), \(b\), and \(x_o\), are defined by the parameters v1, v2, and v3, respectively, for model sig3 (Equation (48)). For model sig4 (Equation (49)), the four symbols, \(a\), \(b\), \(x_o\), and \(y_o\), are entered by means of the parameters v1, v2, v3, and v4, respectively. Numerical fits for the two models to the curves of Figures 21 and 22 are provided in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Hardin/Drnevich model — hardin

The following function was suggested by Hardin and Drnevich (1972):

It has the useful property that the modulus reduction factor is 0.5 when \(\gamma = \gamma_{\rm ref}\), so that the sole parameter, \(\gamma_{\rm ref}\), may be determined (by inspection) from the strain at which the modulus-reduction curve crosses the \(G / G_{\rm max}\) = 0.5 line. Choosing a value of \(\gamma_{\rm ref}\) = 0.06 produces a match to the curve of Figure 21, and a value of 0.234 produces a match to the curve of Figure 22.

| Data set | Default | Sig3 | Sig4 | Hardin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand–upper range | \(L_1\) = -3.325 | \(a\) = 1.014 | \(a\) = 0.9762 | \(\gamma_{\rm ref}\) = 0.060 |

| (Seed &Idriss 1970) | \(L_2\) = 0.823 | \(b\) = -0.4792 | \(b\) = -0.4393 | |

| \(x_o\) = -1.249 | \(x_o\) = -1.285 | |||

| \(y_o\) = 0.03154 |

| Data set | Default | Sig3 | Sig4 | Hardin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay–upper range | \(L_1\) = -3.156 | \(a\) = 1.017 | \(a\) = 0.922 | \(\gamma_{\rm ref}\) = 0.234 |

| (Sun at el. 1988) | \(L_2\) = 1.904 | \(b\) = -0.5870 | \(b\) = -0.481 | |

| \(x_o\) = -0.633 | \(x_o\) = -0.745 | |||

| \(y_o\) = 0.0823 |

Calibration of Degradation Curves

Calibration of the tangent-modulus function involves both a comparison of the function results to the target shear-modulus reduction curve and a comparison to the target damping-ratio curve. The following simple example is provided for illustration and discussion:

In most attempts to match laboratory and numerical damping curves, it is noted that the damping provided by the hysteretic formulation at low cyclic strain levels is lower than that observed in the laboratory. This may lead to low-level noise, particularly at high frequencies. Although such noise hardly affects the essential response of the systems, for cosmetic reasons it may be removed by adding a small amount of Rayleigh damping. It is found that 0.2% Rayleigh damping (at an appropriate center frequency) is usually sufficient to remove residual oscillations without affecting the solution timestep.

Simple Application

The example provided below models a 20 m layer excited by a digitized earthquake to show that plausible behavior occurs for a case involving wave propagation, multiple and nested loops, and reasonably large cyclic strain.

Observations

A method has been developed to use cyclic modulus-degradation data directly in a FLAC3D simulation. The resulting model is able to reproduce the results of constant-amplitude cyclic tests, but it is also able to accommodate strain paths that are arbitrary in strain space and time. Thus, it should be possible to make direct comparisons between calculations made with an equivalent-linear method and a fully nonlinear method, without making any compromises in the choice of constitutive model. The developed method is not designed to be a plausible soil model; rather, its purpose is to allow current users of equivalent-linear methods a painless way to upgrade to a fully nonlinear method. Further, the hysteretic damping of the new formulation will enable users to avoid the use of Rayleigh damping and its unpopular timestep penalties. A comparison of a layered model, assuming nonlinear elastic material using SHAKE, to one using FLAC3D with hysteretic damping is provided in Comparison of FLAC3D to SHAKE for a Layered, Nonlinear-Elastic Soil Deposit.

Practical Issues When Using Hysteretic Damping

The following conditions should be checked when hysteretic damping is applied in a dynamic simulation.

Compare hysteretic damping response to laboratory tests — It is generally not useful to compare apparent damping response from the hysteretic damping model used with a yield constitutive model to damping curves from laboratory results, because laboratory tests are likely to be unstable when shear failure occurs, and therefore unable to provide meaningful results. It is recommended that FLAC3D’s hysteretic response be matched to cyclic laboratory results obtained for a strain range that excludes failure, and that plasticity parameters (e.g., cohesion and friction angle) be matched to static laboratory strength tests. FLAC3D is able to combine the response in both regimes during a typical simulation of seismic response.

Check cyclic strain level — Hysteretic damping not only adds energy loss to dynamic straining, it also causes the mean shear modulus to decrease for large cyclic strains. This may lead to unexpected results (e.g., an increased response amplitude, due to the shift in resonance frequency closer to the dominant frequency of input waves).

Before running a dynamic model with hysteretic damping, an elastic simulation should be made without damping to observe the maximum levels of cyclic strain that occur. If the cyclic strains are large enough to cause excessive reductions in shear modulus for a given modulus reduction curve, then the use of hysteretic damping is questionable—it will be performing outside of its intended range of application. The model properties and input should be checked. If the properties and input are reasonable and the large cyclic strains are limited to small regions, then consider the possibility of excluding hysteretic damping from these regions and using only a yield model in these regions (because the large strains imply that yielding should occur).

Check modulus reduction factor — Even if cyclic strains under elastic conditions are small, the use of a yield model may increase the strains. The hysteretic damping formulation is not intended to be a substitute for a yielding constitutive model. It may be used in conjunction with a yield model (such as Mohr-Coulomb), but conflicts in the domain of application should be avoided if meaningful results are to be expected.

Hysteretic damping is “switched off” for each zone while plastic flow is occurring (including the associated strain accumulation for the hysteretic damping calculation). Note that the stiffness-proportional component of Rayleigh damping is also switched off during plastic flow.

Even so, the apparent modulus used by the hysteretic damping logic may drop to low values,

which can cause unrealistic response. Low (or zero) values of the modulus can be checked by

monitoring the modulus reduction factor, which is the factor by which the small-strain

modulus, \(G_o\), is multiplied for hysteretic damping. (For example, use the FISH

zone variable zone.hysteretic to access the factor for selected zones.)

In some simulations, large modulus reductions have been noticed in areas remote from regions of plastic flow (e.g., near the base of the model). It appears that the use of a single modulus-reduction curve is unrealistic in these cases. There is evidence (e.g., see Darendeli 2001) that degradation curves depend on the mean stress level: for example, at depth (high mean stress), there is less damping and modulus reduction. By making the hysteretic damping depth-dependent, the simulation should be more realistic.

Check initial shear stress state — In laboratory tests, the initial shear stress is assumed to be zero, leading to hysteresis loops that are generally symmetrical. In practical applications, the initial shear stress is unlikely to be zero (for example, within soil elements near the surface of an embankment). The user of hysteretic damping must decide on the best estimate of the initial state of the material, because the hysteretic formulation in FLAC3D depends on the past history of shear strain. Two cases can be identified:

1. If hysteretic damping is activated after a set of equilibrium stresses has been installed, then the initial shear strain will be zero, and cyclic excursions of shear stress will tend to be symmetrical about the starting point.

2. If the initial stresses are built up by straining the model while hysteretic damping is active, then subsequent cyclic excursions of shear stress will tend to be asymmetrical because the initial bias in strain causes the slope of the stress/strain curve to be flatter on the side with higher stress.

These cases are illustrated in the example One-Dimensional Earthquake Excitation of Uniform Layer by modifying the initial model into two further cases.

The approach of using a full static solution while hysteretic damping is active, in order to obtain a compatible starting state for both stress and strain, may be used for more complicated models, such as embankments in which the slope area contains initial shear stresses. One drawback of the approach is that the static solution may involve many diminishing cycles of oscillation as the state of equilibrium is approached. Although these cycles tend to be quite small (and hardly affect the desired stress state), they cause many states to be stored on the memory stack (see Hysteretic Damping Formulation, Implementation and Calibration). These stored states are deleted from the stack early in dynamic loading, but they occupy memory and entail some initial overhead in computer time. It may be possible (in a future version of FLAC3D) to include logic to allow users to flush the stacks at the end of the static initialization, while retaining the latest state of stress-compatible strains for a dynamic simulation with hysteretic damping.

Local Damping for Dynamic Simulations

Local damping (see Mechanical Damping) was originally designed as a means to equilibrate static simulations. However, it has some characteristics that make it attractive for dynamic simulations. It operates by adding or subtracting mass from a gridpoint or structural node at certain times during a cycle of oscillation; there is overall conservation of mass, because the amount added is equal to the amount subtracted. Mass is added when the velocity changes sign and subtracted when it passes a maximum or minimum point. Hence, increments of kinetic energy are removed twice per oscillation cycle (at the velocity extremes). The amount of energy removed, \(\Delta W\), is proportional to the maximum, transient strain energy, \(W\), and the ratio, \(\Delta W/W\), is independent of rate and frequency. Since \(\Delta W/W\) may be related to fraction of critical damping, \(D\) (Kolsky 1963), we obtain the expression

where \(\alpha_{\rm L}\) is the local damping coefficient. Thus, the use of local damping is simpler than Rayleigh damping, because we do not need to specify a frequency. The example Block Under Gravity compares local damping to the other options.

A modified form of local damping—combined damping—may also be used in dynamic mode,

but its performance is unknown. The formulation for combined damping is given in

Mechanical Damping, and the command to invoke it is

zone dynamic damping combined value.

CAUTION: Local damping appears to give good results for a simple case because it is frequency-independent and needs no estimate of the natural frequency of the system being modeled. However, this type of damping should be treated with caution, and the results compared to those with Rayleigh damping for each application. There is some evidence to suggest that, for complicated waveforms, local damping underdamps the high frequency components, and may introduce high frequency “noise.” Also note that local damping is timestep-dependent. Reducing the timestep will reduce the amount of energy removed from the system.

Local damping is not recommended for seismic simulations, because this type of damping cannot completely represent the energy loss of multiple cyclic loading properly.

Spatial Variation in Damping

Rayleigh damping and local damping are both assigned via the zone dynamic damping

command in FLAC3D. A spatial variation in the damping parameters (and the damping type)

can be prescribed by including a range phrase to filter the gridpoints that are used

for the command. For example, if different materials are known to have different fractions

of critical damping, a different value of \(\xi_{\min}\) can be assigned to each

material. This can be demonstrated by modifying the example of a wave propagating in a column. The following example is provided:

Nonuniform damping is specified by using a range in combination with the

zone dynamic damping command. A gradient keyword may be used to vary damping

constants in space. For example, we can modify the Raleigh damping parameters with the

command:

zone dynamic damping rayleigh 0.05 gradient (0,0,-0.05) 25.0 gradient (0,0,-25)