FLAC3D Theory and Background • Constitutive Models

Concrete Model

This concrete model is a plastic-damage model extended and modified from the work in Lublinear et al (1989) and Lee & Fenves (1998) using the concepts of fracture-energy-based damage and modulus degradation in continuum damage mechanics.

Formulations

Modulus Degradation

Based on the concept of the continuum damage theory , the stress \(\sigma\) is linked with the effective stress \(\bar{\sigma}\) [note: in this model, the concept of “effective stress” is a concept in damage theory, which is different from the concept of Terzaghi’s effective stress in fluid-machinal interaction. A variable with a bar on top is in terms of effective stress] by an isotropic damage factor \(D\):

(1)\[\sigma_{ij} = (1-D) \bar{\sigma}_{ij}\]

together with Hookie’s law \(\bar{\sigma}_{ij} = E_{ijkl} \epsilon_{kl}^e\) and additive strain decomposition \(\epsilon_{ij} = \epsilon_{ij}^e + \epsilon_{ij}^p\), it obtains that

(2)\[\sigma_{ij} = (1-D) \bar{\sigma}_{ij} = (1-D) E_{ijkl} (\epsilon_{kl} - \epsilon_{kl}^p)\]

In other words, the nominal elastic modulus is in degradation by a factor of \((1-D)\) from the elastic modulus if relating nominal stress \(\sigma\) and strain \(\epsilon\): \(E \to (1-D) E\).

Damage Based on Fracture-Energy

In this model, two damage variables, one for tensile damage and the other for compressive damage, are defined independently, and each variable is factorized into the effective-stress response and stiffness degradation response parts. Considering a uniaxial tensile or compressive stress state, the state variable \(\chi \in [c,t]\) is introduced. The state is uniaxial tensile for \(\chi = t\) and uniaxial compressive for \(\chi = c\).

The stress is assumed to be determined by the plastic strain. The relation between the uniaxial stress, denoted by \(\sigma_{\chi}\), and the corresponding scalar plastic strain, denoted by \(\epsilon_{\chi}^p\), is assumed as

(3)\[\sigma_{\chi} = f_{\chi 0} \left[(1+a_{\chi}) \exp{(-b_{\chi} \epsilon_{\chi}^p)} - a_{\chi} \exp{(-2b_{\chi} \epsilon_{\chi}^p)} \right]\]

where \(a_{\chi}\) and \(b_{\chi}\) are positive material constants to be determined, and \(f_{\chi 0}\) is the initial yield stress without damage.

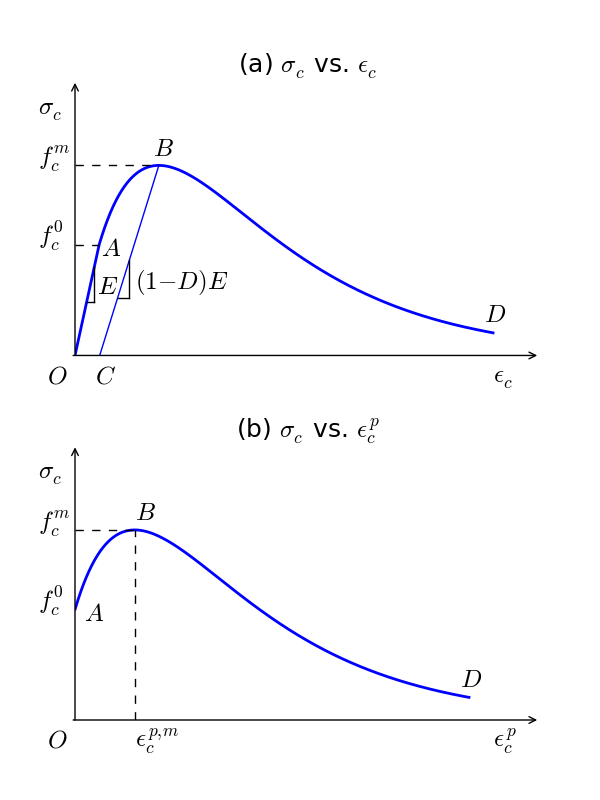

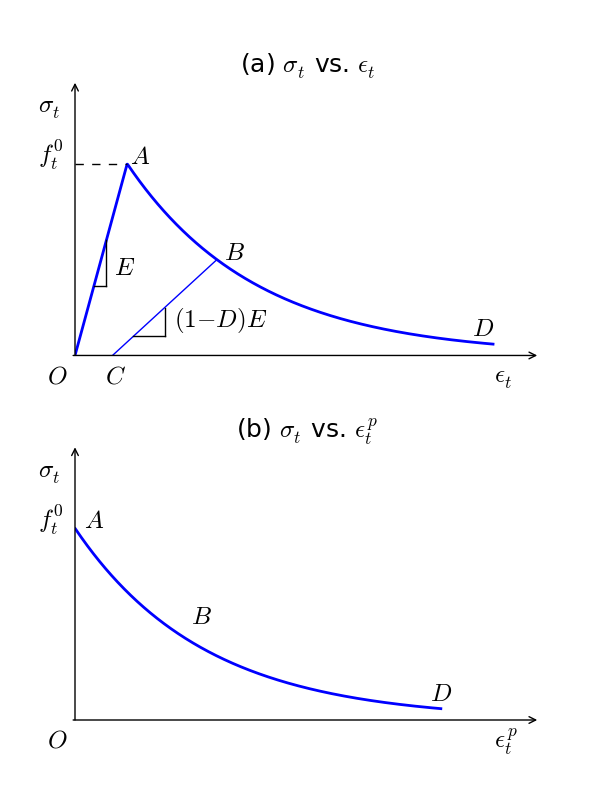

Suppose that we have available experimentally derived stress-strain diagrams in uniaxial tension and compression (top ones in Figure 1 & 2), and that these can be converted into \(\sigma_{\chi}\)-\(\epsilon_{\chi}^p\) curves (bottom ones in Figure 1 & 2). Assume that the area under these curves are infinite and equal to \(g_{\chi}\), define

(4)\[\kappa_{\chi} = \frac{1}{g_{\chi}} \int_{0}^{\epsilon_{\chi}^p} {\sigma_{\chi} \, d \epsilon_{\chi}^p}\]

where apparently \(0 \le \kappa_{\chi} \le 1\). Stress in terms of \(\epsilon_{\chi}^p\), or \(\sigma_{\chi} = f(\epsilon_{\chi}^p)\), can rewritten (Lublinear et al, 1989) in terms of \(\kappa_{\chi}\), or

(5)\[\sigma_{\chi} = f(\kappa_{\chi}) = \frac{f_{\chi 0}}{a_{\chi}} \left[ (1 + a_{\chi}) \sqrt{\phi(\kappa_{\chi})} - \phi(\kappa_{\chi}) \right]\]

where \(\phi(\kappa_{\chi}) = 1 + a_{\chi}(2 + a_{\chi}) \kappa_{\chi}\).

Figure 1: Typical uniaxial compression curves: top - uniaxial compressive stress vs compressive strain; bottom - uniaxial compressive stress vs plastic compressive strain.

Figure 2: Typical uniaxial tension curves: top - uniaxial tensile stress vs tensile strain; bottom - uniaxial tensile stress vs plastic tensile strain.

For stress defined by Equation (3), the quantity \(g_{\chi}\), which denotes the dissipated energy density during the entire process of microcracking, has a closed-form expression of the area under the curve of A-B-D in Figure 1-(b) or 2-(b):

(6)\[g_{\chi} = \int_{0}^{+\infty} {\sigma_{\chi} \, d \epsilon_{\chi}^p} = \frac{f_{\chi 0}}{b_{\chi}} \left( 1 + \frac{a_{\chi}}{2} \right)\]

The initial slope of the curve \(\sigma_{\chi}\)-\(\epsilon_{\chi}^p\) is

(7)\[\left. \frac{d \sigma_{\chi}}{d \epsilon_{\chi}^p} \right|_{\epsilon_{\chi}^p = 0} = f_{\chi 0} b_{\chi} (a_{\chi} - 1)\]

Note that \(a_{\chi} > 1\) implies initial hardening (e.g., when \(\chi = c\)) and \(a_{\chi} < 1\) implies softening immediately after yielding (e.g., when \(\chi = t\)). When \(a_{\chi} > 1\), \(\sigma_{\chi}\) obtain a maximum value (see Point A in Figure 1)

(8)\[f_{\chi}^m = f_{\chi 0} \frac{(1+a_{\chi})^2}{4a_{\chi}}\]

at

(9)\[\epsilon_{\chi}^{p,m} = - \frac{\ln{\left(\frac{1+a_{\chi}}{2a_{\chi}}\right)}}{b_{\chi}}\]

For a curve with initial hardening after yielding which is typical in uniaxial compression, the material constant \(a_{\chi}\) can be back-calculated from Equation (8) by

(10)\[a_{\chi} = 2 (f_{\chi}^m/f_{\chi 0}) - 1 + 2 \sqrt{(f_{\chi}^m/f_{\chi 0})^2 - (f_{\chi}^m/f_{\chi 0})}\]

For a curve with immediate softening after yielding which is typical in uniaxial extension, a simple way is assuming \(a_t = 0\), which leads to

(11)\[\sigma_t = f_{t0} \exp{(-b_t \epsilon_t^p)}\]

and

(12)\[g_t = f_{t0} / b_t\]

Once \(a_{\chi}\) is determined or assumed, \(b_{\chi}\) can be obtained from Equation (6) provided \(g_{\chi}\) and \(f_{\chi 0}\) are known.

Because the capacity for the dissipated energy per unit volume cannot be given as a material property, \(g_{\chi}\) should be derived from other known material properties such as the fracture energy (Lee & Fenvas, 1998). Assuming that the fracture energy in the uniaxial tensile state \(G_{\chi}\) and its counterpart in the uniaxial compressive state are given as a material properties, \(g_{\chi}\) is the specific fracture energy normalized by the localization zone size, also referred to as the characteristic length \(l_{\chi}\), which leads to (Lubliner et al. 1989)

(13)\[g_{\chi} = \frac{G_{\chi}}{l_{\chi}}\]

To maintain objective results at the structural level, \(l_{\chi}\) should be an objective value or assumed as a material property.

Yield Function

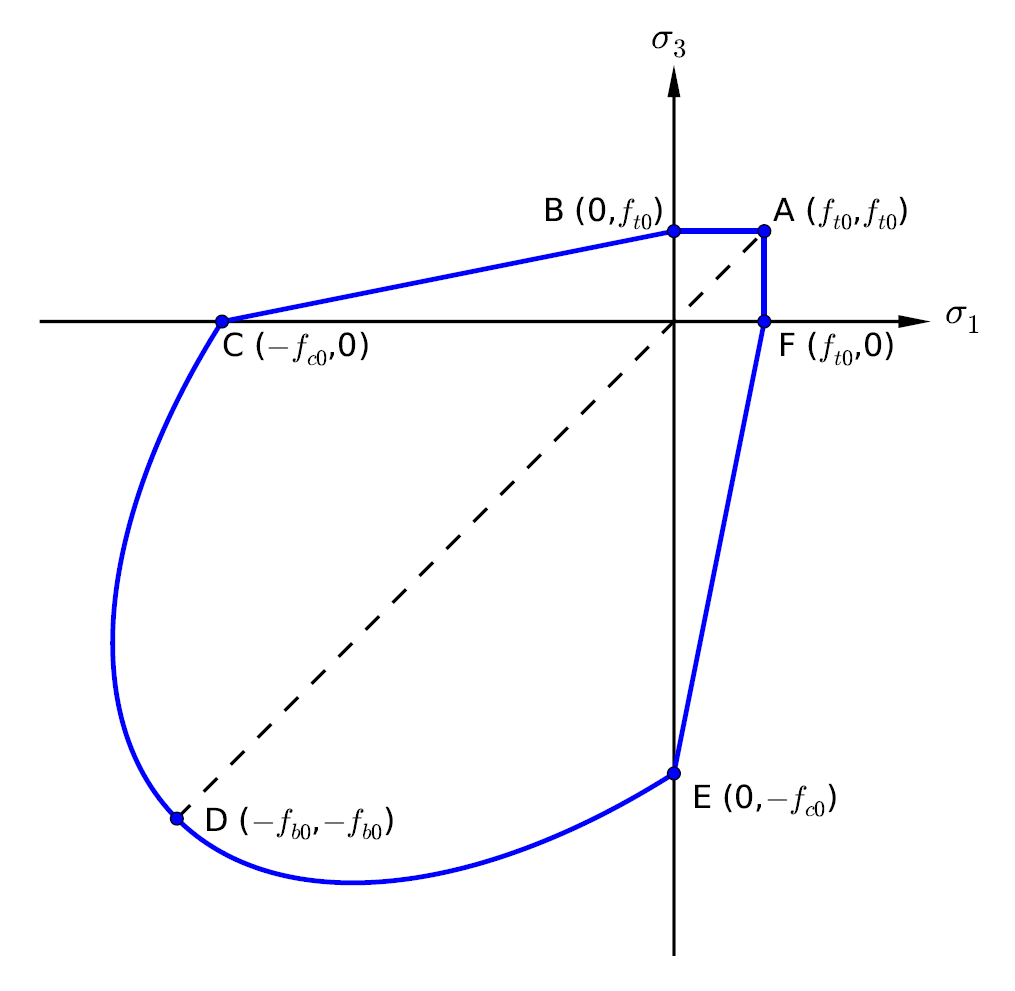

The yield surface is schemed by Figure Figure #model-concrete-yd in the biaxial-stress (plane-stress) space. Note that we assume the principle stresses with the order \(\sigma_1 \le \sigma_2 \le \sigma_3\) and positive for tension. Due to symmetry, only A-B-C-D is considered.

For line A-B, a tension yield criteria is used:

(14)\[f^t (\bar{\sigma}) = \bar{\sigma}_3 - \bar{\sigma}_t = 0\]

For line B-C, a Mohr-Coulomb yield criteria is used:

(15)\[f^s (\bar{\sigma}) = - \bar{\sigma}_t \bar{\sigma}_1 + \bar{\sigma}_c \bar{\sigma}_3 - \bar{\sigma}_c \bar{\sigma}_t= 0\]

For curve C-D, a Drucker-Prager yield criteria is used:

(16)\[f^d (\bar{\sigma}) = \alpha \bar{I}_1 + \bar{q} - (1-\alpha) \bar{\sigma}_c = 0\]

where \(\bar{I}_1\) is the first stress invariant, \(\bar{q}\) is the equivalent shear stress, and

(17)\[\alpha = \frac{f_{b0}/f_{c0} - 1}{2(f_{b0}/f_{c0}) - 1}\]

where \(f_{c0}\) is the uniaxial yield compressive strength and \(f_{b0}\) is the biaxial yield compressive strength. Since usually \(f_{b0} \ge f_{c0}\), \(\alpha\) is in the range of \(0 \le \alpha < 0.5\).

Figure 3: Schematic of initial yield surface in the biaxial-stress (plane-stress) space.

Flow Rule

The plastic strain rate is evaluated by the flow rule, which is defined by a scalar plastic potential function \(g\). For a plastic potential in the effective stress space, the plastic strain is given by

(18)\[\Delta \epsilon_{ij}^p = \lambda \frac{\partial g}{\partial \bar{\sigma}_{ij}}\]

where \(\lambda\) is a non-negative function referred to as the plastic consistency parameter (plastic multiplier).

For yielding at line A-B, an associated potential function is used:

(19)\[g^t (\bar{\sigma}) = \bar{\sigma}_3 - \bar{\sigma}_t\]

For yielding at line B-C, a nonassociated Mohr-Coulomb type potential function is used:

(20)\[g^s (\bar{\sigma}) = - \bar{\sigma}_1 + N_{\psi} \bar{\sigma}_3\]

where \(N_{\psi} = \min(\bar{\sigma}_c/\bar{\sigma}_t, (1+\sin{\psi})/(1-\sin{\psi})\) and \(\psi\) is the dilation angle which is an input material property.

For yielding at curve C-D, a nonassociated Drucker-Prager yield criteria is used:

(21)\[g^d (\bar{\sigma}) = \alpha_p \bar{I}_1 + \bar{q}\]

where \(\alpha_p = min(\alpha, 6\sin{\psi}/(3-\sin{\psi}))\).

Another internal variable set, besides the plastic strain, is needed to represent the damage states. The damage variable, \(\kappa_{\chi}\), is assumed to be the only necessary state variable and its evolution is expressed as

(22)\[\Delta \kappa_t = r(\bar{\sigma}) \frac{f_t}{g_t} \Delta \epsilon_3^p\](23)\[\Delta \kappa_c = (1-r(\bar{\sigma})) \frac{f_c}{g_c} \Delta \epsilon_1^p\]

where \(\epsilon_1^p\) is the minimum principal plastic strain, \(\epsilon_3^p\) is the maximum principal plastic strain; \(r\) is a weight function of the effective principal stresses, which ranges from 0 in pure compressive loading to 1 in pure tensile loading:

(24)\[r(\bar{\sigma}) = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^3 \langle \bar{\sigma}_i \rangle}{\sum_{i=1}^3 | \bar{\sigma}_i |}\]

Evolution of Damage

To model the different damage states for tensile and compressive loading, both \(\kappa_t\) and \(\kappa_c\) are used as independent damage variables. The evolution equations for the hardening and degradation variables are obtained from the factorization of the uniaxial stress strength function, \(f_{\chi}=f_{\chi}(\kappa_{\chi})\), such that

(25)\[f_{\chi} = (1 - D_{\chi}) \bar{f}_{\chi}\]

in which \(0 \le D_{\chi} < 1\) and \(\Delta D_{\chi} > 0\). \(\bar{\sigma}_{\chi} = \bar{f}_{\chi}\) describes the evolution of the cohesion variable used in the yield function, and \(D_{\chi} = D_{\chi}(\kappa_{\chi})\) defines the degradation damage as a function of the damage variable:

(26)\[D = 1 - (1- D_c)(1 - sD_t)\]

where

(27)\[s = s_0 + (1 - s_0) r(\bar{\sigma})\]

with \(0 \le s_0 \le 1\) and so \(s_0 \le s \le 1\) represents stiffness recovery.

The degradation is also assumed an exponent form as

(28)\[1 - D_{\chi} = \exp{( - d_{\chi} \epsilon_{\chi}^p)}\]

where \(d_{\chi}\) are material constants, which can be determined form the unloading-reloading (see B-C lines in Figure 1-a & 2-a).

Material Properties

In this model, two material properties, initial Young’ modulus and Poisson’s ratio, (\(E\), \(\nu\)), or initial bulk and shear modulus, (\(K\), \(G\)), are required to determine the elasticity.

To match the uniaxial compression and tension experimental curves, one straightforward approach is to specify the initial and peak (maximum) strengths (\(f_{\chi 0}\) and \(f_{\chi}^m\)), fracture energies (\(G_{\chi}\)), characteristic lengths (\(l_{\chi}\)), and damages at specific stresses (\(D_c^{peak}\) and \(D_t^{half}\)) in the uniaxial compression/tension states. These input will determine the parameters \(a_{\chi}\), \(b_{\chi}\), \(d_{\chi}\) and \(g_{\chi}\).

Once \(f_{\chi 0}\) and \(f_{\chi}^m\) are known, there are two cases:

if the curve is hardening and then softening (usually in uniaxial compression experiments, see Figure 1), or in other words, \(f_{\chi}^m > f_{\chi 0}\), then \(a_{\chi}\) can be determined by Equation (10).

if the curve is immediately softening (usually in uniaxial extension experiments, see Figure 2), or in other words, \(f_{\chi}^m = f_{\chi 0}\), then \(a_{\chi}\) will be assumed zero.

Once \(G_{\chi}\) and \(l_{\chi}\) are known, then \(g_{\chi} = G_{\chi}/l_{\chi}\), \(b_{\chi}\) can then be determined by Equation (6) so that \(b_{\chi}=f_{\chi 0}(1+a_{\chi}/2)/g_{\chi}\).

Equation (28) can determine \(d_{\chi}\):

for uniaxial compression where the curve is hardening and then softening, then \(d_c\) can be calculated by the the damage at the peak stress,

(29)\[d_c = b_c \frac{\ln{(1-D_c^{peak})}}{\ln{\left( \frac{1+a_c}{2a_c} \right)}}\]

for uniaxial extension where the curve is immediately softening, then \(d_t\) can be calculated by the the damage at the half peak/initial stress,

(30)\[d_t = b_t \frac{\ln{(1-D_t^{half})}}{-\ln{2}}\]

\(\alpha_p\) is a material property determining the dilation, with typical value \(\alpha_p=0.2\).

The biaxial compression initial strength \(f_{b0}\) is requited to calculate \(\alpha\) in Equation (17). Here the ratio \(f_{b0}/f_{c0}\) is instead as an input material property, with a typical value \(f_{b0}/f_{c0} = 1.05{\sim}1.2\).

The stiffness recovery parameter \(s_0\) is usually in the range of \(0 \le s_0 \le 0.2\).

References

Lee, J., & Fenves, G. L. (1998). Plastic-damage model for cyclic loading of concrete structures. Journal of engineering mechanics, 124(8), 892-900.

Lee, J., & Fenves, G. L. (1998). A plastic damage concrete model for earthquake analysis of dams. Earthquake engineering & structural dynamics, 27(9), 937-956.

Lubliner, J., Oliver, J., Oller, S., & Onate, E. (1989). A plastic-damage model for concrete. International Journal of solids and structures, 25(3), 299-326.

concrete Model Properties

Use the following keywords with the zone property command to set these properties of the concrete model.

- bulk f

bulk modulus, \(K\).

- compression-strength f

uniaxial compression peak/maximum strength, \(f_c^m\).

- compression-initial f

uniaxial compression initial yield strength, \(f_{c0}\).

- compression-energy-fracture f

fracture energy in uniaxial compression state, \(G_c\).

- compression-length-reference f

reference (characteristic) length in uniaxial compression state, \(l_c\).

- compression-d f

compression damage parameter, \(d_c\).

- dilation f

dilation angle, \(\psi\).

- poisson f

Poisson’s ratio, \(\nu\).

- ratio-biaxial f

strength ratio of biaxial to uniaxial compression initial, usually in a range of (1,1.25], \(f_{b0}/f_{c0}\).

- shear f

shear modulus, \(G\).

- tension-strength f

uniaxial tension peak/maximum strength, \(f_t^m\).

- tension-initial f

uniaxial tension initial yield strength, \(f_{t0}\). Usually, \(f_{t0} = f_t^m\).

- tension-energy-fracture f

fracture energy in uniaxial compression state, \(G_t\).

- tension-length-reference f

reference (characteristic) length in uniaxial tension state, \(l_t\).

- tension-d f

tension damage parameter, \(d_t\).

- tension-recovery f

stiffness recovery parameter for tension, typical value is 0.2, \(s_0\).

- young f

Young’s modulus, \(E\).

- compression f (r)

Current compression strength, \(\sigma_c\).

- damage f (r)

Current total damage, \(D\).

- damage-compression f (r)

Current damage in compression, \(D_c\).

- damage-tension f (r)

Current damage in tension, \(D_t\).

- strain-plastic-compression f (r)

Current plastic strain in compression, \(\epsilon^p_c\).

- strain-plastic-tension f (r)

Current plastic strain in tension, \(\epsilon^p_t\).

- tension f (r)

Current tension strength, \(\sigma_t\).

Notes

Only one of the two options is required to define the elasticity: bulk modulus \(K\) and shear modulus \(G\), or, Young’s modulus \(E\) and Poisson’s ratio \(\nu\). When choosing the latter, Young’s modulus \(E\) must be assigned in advance of Poisson’s ratio \(\nu\).

Key

- (a) Advanced property.

This property has a default value; simpler applications of the model do not need to provide a value for it.

- (r) Read-only property.

This property cannot be set by the user. Instead, it can be listed, plotted, or accessed through FISH.

| Was this helpful? ... | Itasca Software © 2024, Itasca | Updated: Nov 12, 2025 |